- Guidelines

- IA Rubric

- Faux Pas

- Subject Reports’ General Advice

- Citing your evidence

Guidelines

What is a historical investigation?

It is a written account of between 1,500 and 2,000 words (no more than 2200), divided into three sections, A – Source Analysis, B – Investigation and C – Reflection. The total word count includes in-text citations but not the bibliography.

How many words should there be in each section?

This is no set word limit for each section but one suggestion is:

A – 500 words

B – 1300 words

C – 400 words

What can the investigation be about?

The investigation can consider any genuine historical topic. It can cover topics within the curriculum if you wish and your teacher will approve the choice. No topics that focus on events in the ten years preceding an examination session may be chosen.

When is it done?

You will begin the Internal Assessment during the first semester of Grade 12. The first draft will be due before Christmas and the final piece in January. You will have class time to begin the assessment.

Example of Title Page

Guidance – Section A

The following advice is from ThinkIB, Active History, the advice of other teachers and myself.

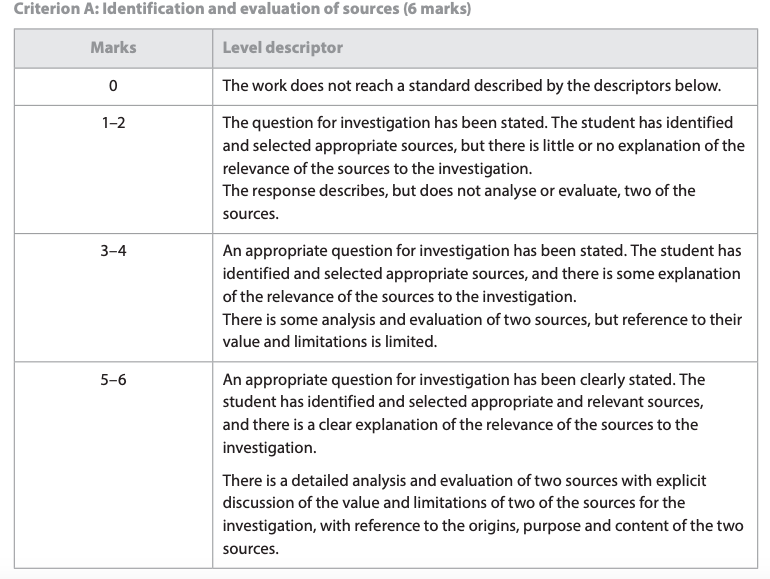

Criterion A

In this section, students need to:

- Identification and evaluation of sources.

- State the research question (RQ). This should be a narrow focus. Questions about the causation or consequence of an event are probably too large for the IA. Make sure the RQ is an actual question, use ‘two what extent’ or ‘how’ rather than ‘discuss’ or ‘analyse’.

- Why is there an investigation/ controversy/ debate about the issue you have chosen?

- Identify the two sources that they are going to evaluate and state why these sources are relevant to their investigation (they should be named specifically). It is advisable to select one primary and one secondary source although it is not compulsory.

- If you are using a map or cartoon, make sure it is visible in this section.

- Why did you select the two choices? How are they relevant to the investigation?

- Evaluate the two sources in detail referring to the values and limitations of the origins, purposes and content. Focus on balance too, give equal weight to both values and limitations.

- Do not describe or summarise the sources!

- Use words such as value, limitation, hindsight, historian, bias, archives, provenance.

- When using bias, consider how you use it. For example, how is the author biased? Be Specific. You may also think about TOK – why is the author or source bias? What are the influences? Lastly, how much bias is there, the entire article or source?

- Research the authors of the source. Think about nationality, specialism, the context in which they are writing/producing, gender, age, education etc.

- Section A builds on the skills that they will already have developed for Question 2 of Paper 1.

- Origin – What are the factors which influenced the publication/ production of the source? Think about political, economic, social or military events. This requires a lot of research to find out the answers. For example, if you find an article that was published in Munich in 1939, you can identify several influences,

a. Munich was a strong Nazi city. Although the March 1933 election only gave 45-50% of the vote to the NSDAP in the city, it had become the capital of the movement and held the important Munich Conference in 1938. This may have influenced the objectivity of the article as the author could be inspired by events or fearful of recriminations if they were critical of the government.

b. Even if the author was sympathetic to minorities such as the Jews, events such Kristallnacht in 1938 or the Nuremberg Laws of 1935 would deter them from writing freely.

c. Even though Hitler won only one-third of the vote in the November 1932 election, his popularity and reputation were enhanced within Germany because of his foreign policy successes (Saar 1935, Rhineland 1936, Anschluss 1938) and a return to seemingly economic growth (though the Nazi propaganda was clearly a factor in people’s perceptions). This could influence the content and analysis of the article in favour of Hitler.

- Sentence starters:

This investigation seeks to answer the question “…

In order to maintain a clear focus, the study will (only) analyse…

One key source managed for the investigation was…

This was chosen because…

The source was written by….which is a major value/limitation for this investigation as…

It was produced in…., making it a primary/secondary source for this study. This is a value/limitation as…

The source is a (e.g. speech), which is also a value/limitation to this study because….

The purpose of the source is to inform/persuade the reader about…This makes it valuable/limited to this investigation as….

The source’s content is particularly valuable to the source, for example…

Aim for one-hundred words for the introduction and two-hundred for each source.

Example of an introductory paragraph

Subject Report May 2022

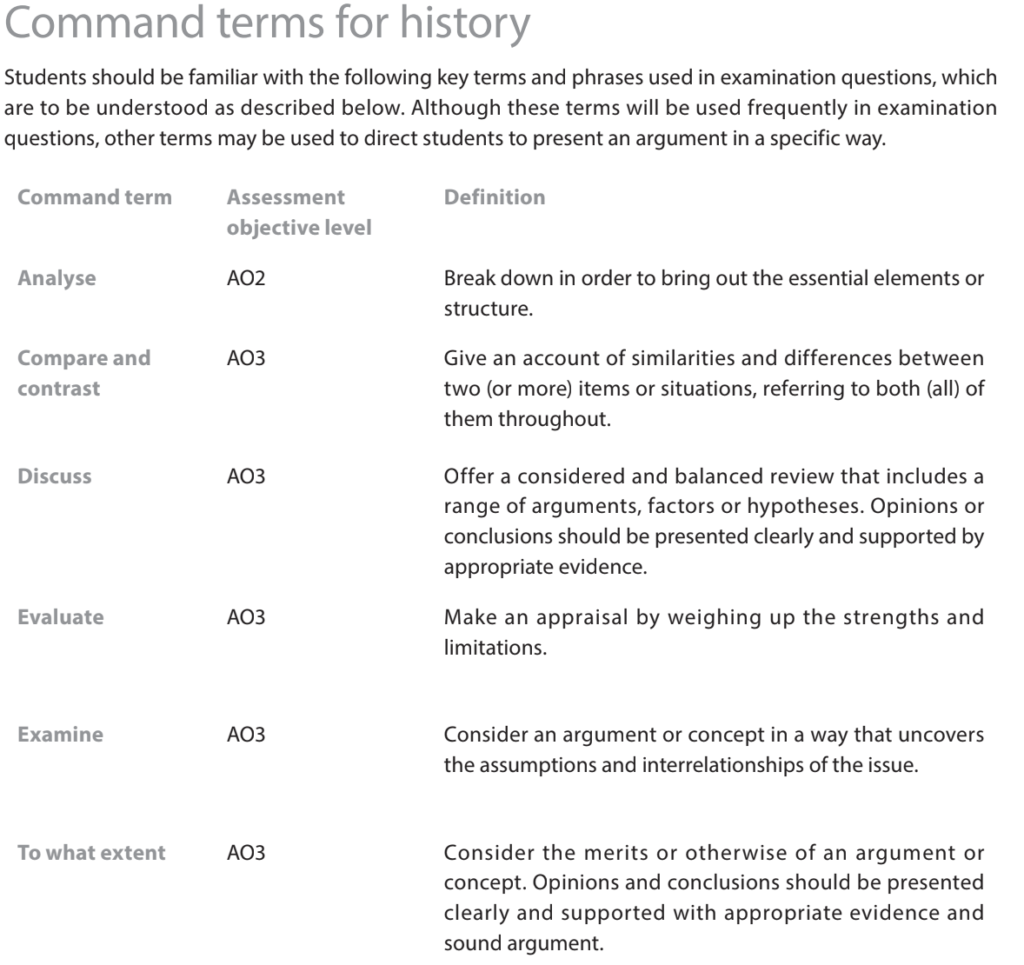

- Ensure you use a command term from the History Guide. See image below.

- Ensure the IA question is not too narrow, it must allow for debate.

- Avoid IA questions which ask for a narrative.

- Avoid using generic or simple sources such as encyclopedias, textbooks or YouTube videos.

- If using ‘orthodox’ or ‘revisionist’ historians, you must give explanations for these labels.

- Do not write ‘could be a limitation’. It either is or it is not for Section A!

- Do not assume nationality means bias or an eye-witness account means value, this is too simple.

- You choose a source so never argue that one of its limitations is the lack of information…the limitation is you as you chose it!

- Aim for two types of sources.

Subject Report May 2023

- Largely repeating the above: avoid simple and generic sources, orthodox v revisionist historians.

- Identifying values a strength, limitations more challenging.

- Nationality does not automatically with a school of thought.

- If a source could be a limitation, who for, how? But as far as possible, aim for ‘it is a limitation because…’

- Think about what sources are available to the historian before choosing a topic.

- Aim to select a school of thought for this section too.

Guidance – Section B

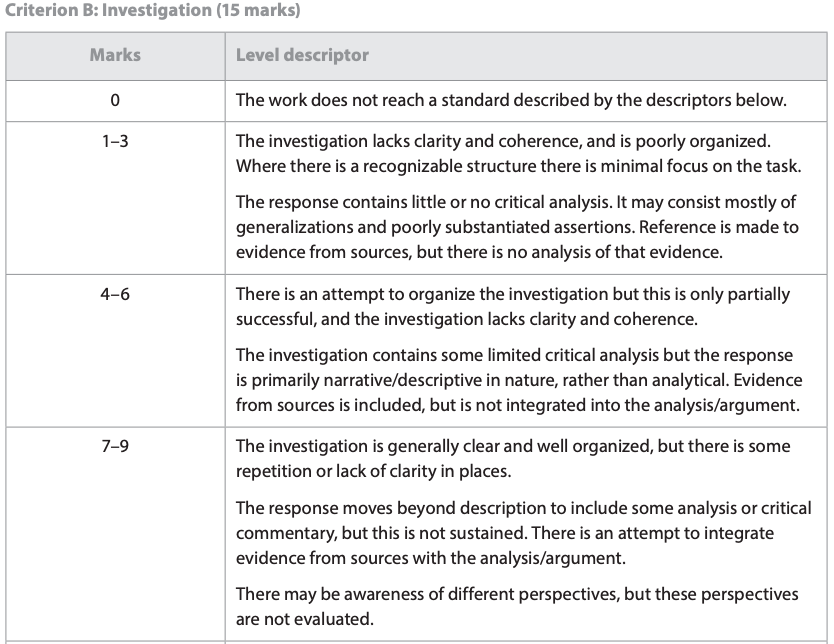

Criterion B

This is the main investigation. As such it needs to include the following:

- a clear focus on the research question. As with Papers II and III, you should link your analysis to the question and/or thesis statement.

- critical analysis of the issue

- different perspectives, explain why. Aim to be balanced.

- reference to a range of sources, including those in Section A.

- ensure you write a bibliography which includes all the sources you have used.

It is important that you thoroughly research your topic. You should aim for academic sources rather than superficial websites. For example, use JStor rather than history.com. The latter is useful for background information but the material may not have been thoroughly investigated and the content is geared towards a specific audience. Furthermore, it does not always include the author.

As with any essay, it needs to be clearly structured and end with a conclusion that addresses the question and which is consistent with the argument that has been put forward in the main body of the investigation. It is recommended that you include THREE articles or books and TWO websites to reference within the investigation. You have also included intext citations.

DO NOT

- Use extensive footnotes to ensure you are within the word limit. If the information is relevant, make sure it is part of the investigation.

- Write the conclusion with a new argument or piece of evidence.

The following advice is from Active History.

Introduction (c. 100-150 words)

• Set the scene / generate reader interest by establishing why this question was important at the time, and remains relevant today.

• Summarise the different historical perspectives that exist in relation to the question.

• Outline how the essay will be structured, and the main conclusions that will be reached.

Main Body (c. 1000-1100 words)

- Evaluate the evidence for several different perspectives in separate paragraphs.

- Within each paragraph, start with a clear topic sentence which is clearly focused on the question. Then explain it with carefully selected and properly referenced evidence (use quotes as necessary).

- Ensure that you stress the value of the evidence you use, but also acknowledge its limitations, with reference to Origin, Purpose and Content as appropriate.

Conclusion (c. 100-150 words)

Provide a direct answer to the question you set yourself by synthesizing the main points of the essay. In particular, stress which historical perspective you agree with most and why, and which historical perspective you reject and why, or whether you think it is possible to accept different elements of different perspectives to provide a new interpretation.

Example of how to begin the Investigation.

Subject Report May 2022

- Strong IA’s focused on the question throughout.

- Evaluating the perspectives remained the most difficult skill for even the better IA’s.

- Still too many narratives, the investigation needs to be analytical.

- Avoid explaining or discussing counterfactuals such as ‘he could have won if…’.

- Make sure every paragraph is answering the question.

- Aim to discuss historiographical trends or schools of thought.

- Advisable to discuss the methodology of the historians here too.

Subject Report May 2023

- Some excellent investigations but a concern is how students struggle to evaluate perspectives.

- Ensure all the data and evidence answers the question.

- Similar to last year, avoid counterfactuals.

- End the investigation with a conclusion rather than a summary.

- As with Section A, include a school of thought. This may make it easier to evaluate the perspectives.

Guidance – Section C

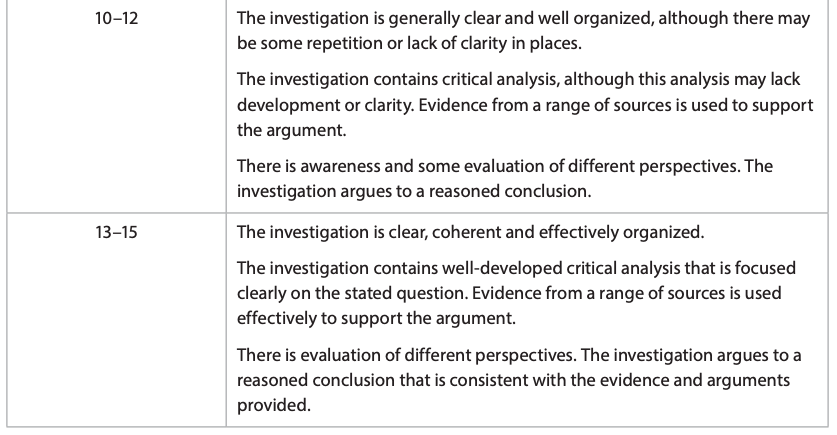

Criterion C

Criterion C is the refection part of the essay. The refection is very different from the reflection part of the Extended Essay or for that done as part of CAS. It is a reflection about the work of a historian and should show what the student has learned about the methodology of a historian and also about the challenges faced by a historian. In this sense, it is linked very much to TOK.

It is a good idea to work with the TOK teachers before doing this section to check that history has been covered in TOK. It is important that students link their thoughts on the methods/challenges of historians to their actual essay and do not just talk generally about methods of and the challenges facing historians.

- If candidates state that finding relevant information on the topic was a challenge, credit will not be awarded. However, if they explain that such a challenge is also faced by historians and can effectively link it to their investigation, then their point could be made relevant.

Example of how to begin the Reflection.

Further guidance is from ActiveHistory and IB Historyia. I recommend you refer to both to help both your research and analysis.

The Role of the Historian

When writing Section C, it is recommended that you use one of the following historians in your analysis. But make sure it is relevant to your investigation, do not just add the perspective of the historian.

- When identifying problems researching your topic or writing the investigation, don’t worry, historians have all been there before. Several respectable historians explain the problems of studying and writing history below. Their views may help you with your investigation and reflection for the IA.

- John Lewis Gaddis (Professor of Military and Naval History at Yale University) compares the examination of history to that of a landscape, it cannot be visited by anyone in the present because it will change and one’s interpretation of it can never be the same.

- Historians, he writes, “can never actually rerun history any more than astronomers, geologists, and paleontologists, and evolutionary biologists can rerun time.” Thus, history can only represent the past, and no matter how close the representation resembles the reality, the fit can only be provisional. Yet, even poor representations, as time goes by and as witnesses disappear, often become the reality. Historians may make the past legible but in doing so they also imprison it. While this is not done with malignant intent, the reader would be well served to know how a particular history was constructed. (https://www.nps.gov/CRMJournal/summer2004/reviewbook4.html)

- Leopold von Ranke argued that the purpose of history was to instruct the present for the benefit for future ages, to show what actually happened. But that one should not judge the past in the context of today. Whatever decisions they made was thought best at the time. There should be no moral superiority of contemporaries.

- Suzannah Lipscomb agrees, arguing that context is paramount if passing judgement.

Without context, it is impossible to judge history. In the link provided, Lipscomb uses English monarch King Henry VIII as the example to prove her arguments.

- Yet she acknowledges that the purpose of history too, ‘…I would venture that judging the past is one of the primary ways that the public engages with history’. To this, judgements have to be made, not doing so according to Lipscomb would negate the writing of history in the first place.

- But yet historian Donald Bloxham argues differently, he argues that one should make a stance. He further argued that a historian should not just rely on published sources but should seek those who have not been. Aim for primary sources as much as possible. This view is supported by Hilary Mantel in that the past changes a little every time we retell it…actually a good name for an educational website! Yet historians still prefer to use the works of earlier historians rather than sources. To this end, what is the purpose of history?Is the object of history merely to fill in the gaps of knowledge?

- And, if the gaps have already been filled, should there be a further study? Yes, because new techniques and discoveries in archeology meant that previous studies can be further analysed. But who chooses what history to study? Nazi Germany is possibly the most popular history course in the world and the subject of countless books and documentaries. Is this because it is important or because it is what the public want?

- If, according to Benedetto Croce, ‘All history is contemporary history’, so all history is written from the perspective of the present. If a historian is aware of this how does he avoid it?

- George M. Trevelyan argued that history was a mixture of the scientific, (research), the imagination or speculation, (interpretation), and the literary, (presentation). Can you see the values and limitations if this perspective is accurate?

- History has been dominated by the nation-state, how one lives with another. Celebrating one’s own was common, this was especially true during the period of the First World War, historians writing in defence of their own nation.

- Richard Evan’s In Defence of History explains how history became more a science in the past few centuries.

- This article which reviews Making History: The Storytellers Who Shaped the Past contains useful references to historians and the study of history.

- There are some useful general websites and articles to read in addition to professional historians. These include Is a historian a judge?, The Detective versus the Historian, the excellent Alpha History – Problems of History and Lost in History.

- Why do people write diaries?

Subject Report May 2022

- This remains the most challenging section.

- Too many students discuss their personal experiences rather than the methodology of the historian, these should not be part of the reflection.

- Aim to discuss the different ways history is achieved. For example, analysing primary written or statistical sources, using oral testimonies etc.

Subject Report May 2023

- Similar to last year, too many students discuss their own personal experiences.

- Must focus on the methodology of the historians and the sources they have access to and/or use. For example, what oral histories are used and how reliable are they?

IA Rubric

Faux Pas

- Consulting mediums as sources.

- Using confidential information in an IA, i.e. police sources

- To what extent did the US drop an atomic bomb on Japan?

- To what extent did the British evacuate their troops from Dunkirk?

- Ignoring the teacher’s advice!

- Using textbooks as sources.

Subject Reports’ General Advice

- Citations must be 100% accurate…use the correct guide then proofread, proofread and proofread.

- Develop a Research Question that is answered with evidence. It should not be answered hypothetically.

- When proofreading, ensure all of your investigation answers the research question. Some IA’s have digressed into other topics.

- Use selected academic evidence which is relevant to your topic. Avoid using generic history sources such as history.com or encyclopedias.

- You must explain the relevance of your two sources to the investigation.

- Primary sources are not more valuable just because they are primary.

- If you use revisionist or orthodox historians, explain what these are.

- If you write that an author is biased because of nationality (a possible limitation), you must give a specific example.

- If you write that a limitation is a translation, again you must be specific. It is too simple to write that a translation is inaccurate.

- Compare and contrast your sources with others, this is the evaluation of perspectives.

- Develop a conclusion or judgement at the end of Section B, not a summary of what you have written. ‘The sources/evidence in this investigation prove that…’.

- For Section C, focus on the role of the historian, not the personal problems you faced. If you think you need more sources, specify which.

Citing your evidence

Here are some resources you may find useful:

Easybib MLA9 updates and highlights