Austria-Hungary

- Austria lost a war against Prussia in 1866. To maintain power in Europe, they joined Hungary to form the new country, although power was largely in Vienna and not Budapest.

- German Chancellor Bismarck decided to keep Austria in check (and to avoid isolation) by becoming allies with them in 1879. He signed the Dual Alliance where both countries agreed to support each other if attacked by Russia and to maintain neutrality if by another.

- Austria-Hungary was an empire with many nationalities, religions and cultures. Consequently, it was a difficult balance to maintain control over them. Force was often used as the tool to ensure this.

- The empire rested on former glories, it was no longer the military force is used to be (the first half of the 19th century) although many in the country believed it was.

- The decline of the Ottoman Empire led to power vacuums and the rise of nationalism in the Balkans. This led to instability in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, particularly amongst the Slavs. For both political and military reasons, Austria-Hungary wanted influence over the Balkans. Moreover, any country that stirred up the Slavs such as Serbia needed to be stopped.

- Economically, the empire did not rival the other major European powers.

- Militarily, the empire understood the power of its ‘ally’ Germany. It needed her support in case of Russian aggression and had to demonstrate loyalty too.

- Ideologically, Germany and Austria-Hungary were monarchies with empires. It was not inevitable that these two countries would become allies but perhaps preferable to the republics of France and Britain. This is supported when allying with Italy, another monarchy, in 1884, with the Triple Alliance.

Austria-Hungary to blame because…

- Conrad, the Austrian Chief of Staff from 1906 to 1917, continued to push for war before and up to 1914. Serbia was his preference, especially after their success in the Balkan Wars, but he even pushed for war against Italy, who was an ally.

- The most often used piece of evidence to argue for Austro-Hungarian blame is their ultimatum given to Serbia after Franz Ferdinand was assassinated. It was seen at the time as unjust and unacceptable to any sovereign country. Arguably, it was designed for the Serbians to refuse its conditions and therefore give a pretext for war.

- With Germany offering their blank cheque, Austro-Hungary were confident they could attack Serbia even if Russia came to their aid. Of course, one can blame Germany for this but Austro-Hungary did not have to acept their aid, ensuring that any conflict could be localised.

- Austro-Hungary had annexed Bosnia in 1908, much to the annoyance of Russia and Serbia.

- Moreover, as several of my students have argued, Austria-Hungary’s actions since 1878 has resulted in a growing Serbian nationalism. However, this could mean blaming Serbia too. You can read more about this here.

Britain

- British foreign policy in the 19th and 20th centuries was dominated by the empire. It guarded and maintained their colonies and dominions through the navy and diplomacy. If there was a trouble spot in their empire, the Royal Navy could bring troops and supplies to put it down.

- For this reason, the bulk of the Royal Navy was spread out around the world, not protecting the islands in the North Sea. Therefore, if any European country significantly increased the power of their navy, especially in Northern Europe, this could change the balance of power on the continent and become a direct threat to British security. She could either reach an agreement with the growing naval power to limit their growth, become an ally (Anglo-Japanese Alliance 1902), or stop their production by force (arms race). The latter could be seen as an aggressive policy and put the blame on Britain for escalating tension in Europe.

- Furthermore, Britain became embrolied in the rivaly between France and Germany over the issue of Morocco. The two flashpoints, 1906 and 1911, saw Britain act forcefully and escalate the tension between themselves and Germany.

- Britain’s empire grew with the help of their 19th-century foreign policy ‘splendid isolation‘. The continent of Europe had had hundreds of wars in its history and would probably have more if Britain had not stayed out of European conflicts as much as it did. Britain opted to focus its ambitions beyond Europe to improve its trade and power, largely ignoring the problems on the continent.

- Britain was to blame because it felt it could not remain neutral. If Germany was victorious it would have hegemony across Europe and weaken the British Empire. Particularly if Germany held the northern ports of France, Belgium and the Netherlands. The Royal Navy would have to protect the shipping lanes around the British Isles rather than the empire.

- Britain could have also threatened to intervene militarily during the July Crisis but did not do so. This may have deterred Germany from fighting although this is a huge ‘what if’.

- Addtionally, should France and Russia be victorious, they may be hostile to their former ally and weaken the empire.

- Niall Ferguson argues in the Pity of War that the British foreign secretary, Edward Grey, was anti-German and reluctant to negotiate with them over the problems in the Balkans. However, Robert Massie argues the opposite, Grey was the finest foreign secretary Britain had ever had.

- Finally, why did Britain declare war on Germany for the invasion of Belgium in 1914? They cited the Treaty of London in 1839 but was this really a legitimate reason. Was just an excuse instead? One could argue that military action against Austro-Hungary and Germany in August 1914 directed attention away from Britain’s issue of Ireland. This had divided British politics and there was a fear of civil war. To unite the government behind one cause, perhaps Edward Grey and the Prime Minister, Asquith, opted for war instead.

France

- France wanted revenge for its defeat in the Franco-Prussian war of 1871 and the return of Alsace-Lorraine. It had managed to escape the Bismarckian noose which he had put onto France after this conflict by allying with Russia in 1894 (Dual Entente/ Alliance) and signing an agreement with Britain in 1904 (Entente Cordiale). In doing so, France improved her security situation but perhaps also provoked Germany to act. After all, an alliance involving France and Russia would make Germany fight on two fronts if war arose.

- France did have a military alliance with Russia but perhaps it had engineered this to provoke a war with Germany. It gave huge loans to Russia for which they were able to build huge railways to Europe. These could transport thousands of Russian troops to central Europe.

Germany

- After unifying Germany after the Franco-Prussian War, Chancellor Bismarck’s policies were designed to maintain its position in central Europe. He was clearly the dominant figure in the German government even though Kaiser Wilhelm I was his superior. Watch the video below to understand more.

- Germany to blame because of their ‘blank cheque’, imperial ambitions and aggressive foreign policy. Fritz Fischer, a German historian, argued that the ‘blank cheque’ should mean that they take the majority of the blame for starting the war.

- AJP Taylor and Gerhard Ritter argued that the Schlieffen Plan was to blame for the war. It had rigid timetables to adhere to which left little time for negotiation if war broke out. Other countries did not have the same plans so were more flexible.

Italy

- It is unlikely Italy can be blamed for the conflict because it did not take part in the fighting in 1914. However, as it signed up to the Triple Alliance in 1882 and conducted an aggressive imperialist policy against Abyssinia (1896) and Libya (1911-12). This may have escalated the rivalry over African colonialism between the Europeans.

Russia

Russia turned its attention to Europe instead of Asia after their defeat in the Russo-Japanese War. It then entered into an alliance (non-military) with Britain and became a member of the Triple Entente. This would obviously antagonise the Triple Alliance powers and increase tension in Europe.

Furthermore, foreign minister Isvolsky attempted to take Constantinople for Russia whilst reaching a deal with Austro-Hungary (Bosnian Crisis, 1908). This clearly ignored their ally, Serbia’s, wishes so Russia’s foreign policy was clearly selfish. Admittedly, there is little evidence to prove the Tsar knew of this deal but one could argue otherwise. Russia may have inflamed the July Crisis because she wanted revenge for her defeat during 1908.

Despite the events of the Bosnian Crisis, Russia was still seen as the protector of Serbia. As a result, if she has influence over the Balkan state, why was it allowed to grow so quickly (especially the Balkan Wars) and worsen the tension with Austria-Hungary? If Russia wanted peace in eastern Europe, arguably she could have been more forceful in limiting the growth of Slav nationalism in the Balkans.

In 1914, Russia mobilised her army after Austria-Hungary did so but she was not at war yet. Why escalate the situation? Did the Tsar want a war or was he merely mobilising his forces to deter aggression?

All

All countries were to blame because you always have a choice to not go to war, Italy proved that.

The militarist policies were to blame because the Great Powers had spent so much money for decades building up their armed forces. This led to two key policies, the first was the confidence this gives to the government to act aggressively. The second is that countries became afraid that they had to act decisively in 1914 otherwise a rival could overtake them in the arms race.

Historians and Historiography

World War One: 10 interpretations of who started WW1

Max Hastings – Catastrophe, 2013

Margaret MacMillan – The Road to 1914, 2013

Margaret MacMillan “there is still no historical consensus about the origins of the war, and particularly about who is to blame for it. “The consequences were so great, but we still don’t understand how it started.”

Christopher Clark wrote Sleepwalkers in 2013.

- The Serbian government was not complicit in the assassination. The president knew that arms were being moved from his country into Bosnia but knew that any violence against Austro-Hungary would bring harsh consequences.

- The great majority of statesmen in 1914 would not expect a large European war. They had overcome crises such as Morocco, Bosnia and the Balkans wars and remained peaceful. Perhaps these events may have given these statesmen a false sense of security.

- Clarke focuses on ‘how’ a peaceful Europe went to war in July 1914, not ‘why’. His rationale is that the latter assumes blame, the focus of the debate since 1914. Clarke wanted to do something different.

- He argues that government foreign policies within the Great Powers switched between individuals and departments because of the pressure they were put under. Therefore, there was confusion in these governments about what they should do.

- 1911 Italian-Libyan War arguably the first war of aggression in which all others followed. This was the first war involving aircraft and bombs dropped from them. This was an example of how Europe was not at peace before 1914.

- Sleepwalkers was well-received because it gave a different perspective. However, criticism included that he was trying too hard to find a way of exonerating Germany.

Richard Evans

- Bismarck’s military policies of the 1860s were to achieve German unification under Prussian leadership. He did not want expand further as this would change the balance of power too much and may bring reprisals. This was unlike Kaiser Wilhelm II’s position who did not see the consequences of aggressive acts.

- The defeat of Russia in the 1905 Russo-Japanese War influenced them to focus on Europe instead. This made Austro-Hungary(A-H) anxious.

- The assassination of Franz Ferdinand gave A-H the reason or excuse to punish and weaken Serbia. They had wanted to do this for several years. But were anxious about the role of Russia so wanted support. Germany offered the blank cheque.

- Evans does not see the assassination as a German excuse to take on Russia. Germany wanted a localisation of the conflict. But the Austro-Hungarians did not act quickly and this decreased the likelihood of localisation. The acceptance by Serbia of much of the ultimatum was thought by the Kaiser to have avoided war. But A-H attacked anyway.

- France saw an opportunity to take revenge for Alsace-Lorraine. But A-H had no plan not to invade.

David Reynolds (37 Days), Niall Ferguson (Pity of War), Margaret MacMillan (Road to 1914)

In order or appearance,

Niall Ferguson – There was there no winner of the First World War such was the casualty count among the participants? Moreover, he criticises the British government (citing his book The Pity of War, 1998) for entering into the conflict. The Cabinet was deeply divided and took the decision despite not being prepared to fight a war. However, he also adds that an argument could be made for the European leaders and upper-classes deciding upon a war to rid themselves of the threat from the socialists. A war would centralise power and a victory would make it last.

Later, Ferguson argues that the September Programme would not have been published had Britain not entered the war in 1914. Furthermore, Germany miscalculated in its strategy; it was never their intention to fight Britain. But he also offers a controversial view, that if Britain did not fight, and Germany won the First World War as a result, in the long-term she would be weaker. Controlling all of Europe, especially the east, would prove very difficult and very expensive. This would allow Britain to get stronger, similar to the Napoleonic Era.

Margaret Macmillan argues that the countries who took the fateful decision to fight in 1914 were lacking both imagination and courage. They claimed there was no choice but to fight. Albeit with hindsight, they were wrong.

Allan Mallinson explains that Britain only got involved because of the German invasion of Belgium. It broke the 1839 Treaty of London and the Cabinet felt that reneging on the rules of the agreement would severely affect their standing in the world.

David Olusoga argues that the crimes and behaviour of the German army made the war worth fighting. He argues that their genocide in Africa and 1914 September Programme meant that the British had to declare war on Germany.

The famous AJP Taylor on the causes of the First World War. He argues railway timetables were to blame! Barbara W. Tuchman’s, below, agrees.

Barbara W. Tuchman’s Guns of August, published in 1962, argues that the alliance system and the railway timetables designed for future military operations were to blame for starting the First World War. The latter focuses on the Schlieffen Plan and the requirement to defeat France quickly, moving hundreds of thousands of troops in the process, before attacking Russia.

Raffael Scheck argues that Germany was to blame for the First World War because in 1914 “The German government, in particular, felt under increasing pressure from the generals and from right-wing opinion to wage war at the next feasible opportunity. Diplomatic means to counteract the encirclement of the country had proven counterproductive and seemed exhausted”. Raffael Scheck and German responsibility

Robert Massie blames Kaiser Wilhelm II for much of the growing tension between the European powers. Furthermore, German politicians are also criticised, although many merely press ahead with an aggressive foreign policy to win favour with the Kaiser.

On the other hand, Paul Gottfried argues that “The German fear of “encirclement [Einkesselung]” was justified, and particularly after the Franco-Russian alliance in 1894″. Furthermore, “The First World War was avoidable on both sides; and it was the old order that recklessly blundered into it, although that order hastened its own destruction by unleashing the war. It has also been the Right that has typically regretted the First World War as the destroyer of an older and better world.” Innocence of Germany

Niall Ferguson agrees with Gottfried in that he blames Britain and Edward Grey, the Foreign Secretary, for the escalation into global conflict in 1914. “Britain’s intervention in 1914 was “nothing less than the greatest error of modern history,” because Germany in fact did not pose an essential threat to British interests. So Ferguson indicts London, because “it was the British government which ultimately decided to turn the continental war into a world war, a conflict which lasted twice as long [as] and cost many more lives” than it would have if only Britain had not stepped in the way.” Was the Great War Necessary? The Atlantic

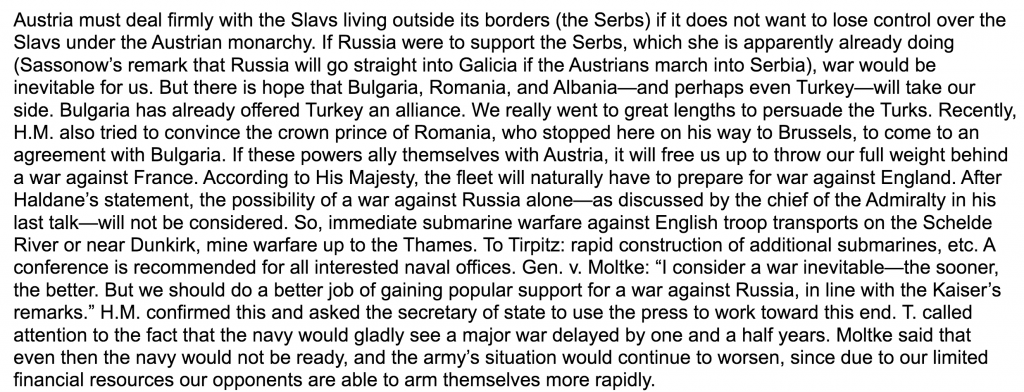

Graham Goodlad cites Fritz Fischer in that he drew attention to the War Council of 1912 (see below). The political difficulties involving the rise of the SDP were discussed. A war where Germany became dominant in Europe, (even more so – my words), would negate their influence, (I don’t agree). Graham points out that many conservative historians refute this, (he does not say when, presumably recently, but they would if called conservative).

Fritz Fischer famously blamed the Imperial German Government for the First World War. ‘Fischer was given access, in the 1950s, to the East German archives at Potsdam, where he came across an explosive set of files relating to war aims and annexationist plans that the Reich government had drawn up in World War I. It was not merely the extent of Germany’s territorial ambitions that moved him to develop his provocative hypotheses, but also the suspicion that the German government might have started the war in the first place in order to realize its expansionist program on the European continent.’ https://www.historians.org/publications-and-directories/perspectives-on-history/march-2000/in-memoriam-fritz-fischer

Annika Mombauer, author of The Origins of the First World War: Controversies and Consensus argues that Fischer was right and that Germany had tried to rewrite history by blaming all the European powers for the conflict in 1914.

Opposing Fischer was Gerhard Ritter.

Historiography of World War One

Guns of August – The Daily Beast

Guns of August – Hoover Institute

Gary Sheffield argues that the First World War has largely been misrepresented by contemporary society. He explains that the 1961 play ‘Oh, What a Lovely War‘, influenced by the peace movements of the 1960s, criticised the fighting of the war and even the rationale to fight it. The British television series ‘Blackadder‘ (see below) from the 1980s adds to this perspective. But Sheffield argues that, just as the Nazis wanted to build a European empire, the Kaiser did too. Hitler was clearly more of a threat but both ‘nations’ had to be defeated. Without Germany’s aggressive pre-1914 policies, conflict could have been avoidable.

Causes of the First World War – A Preventable War

Debate – Britain should not have fought in the First World War

BBC – 37 Days