- Timeline 1839-1930

- 1839 to 1931

- 1931 to 1937

- Why war in China?

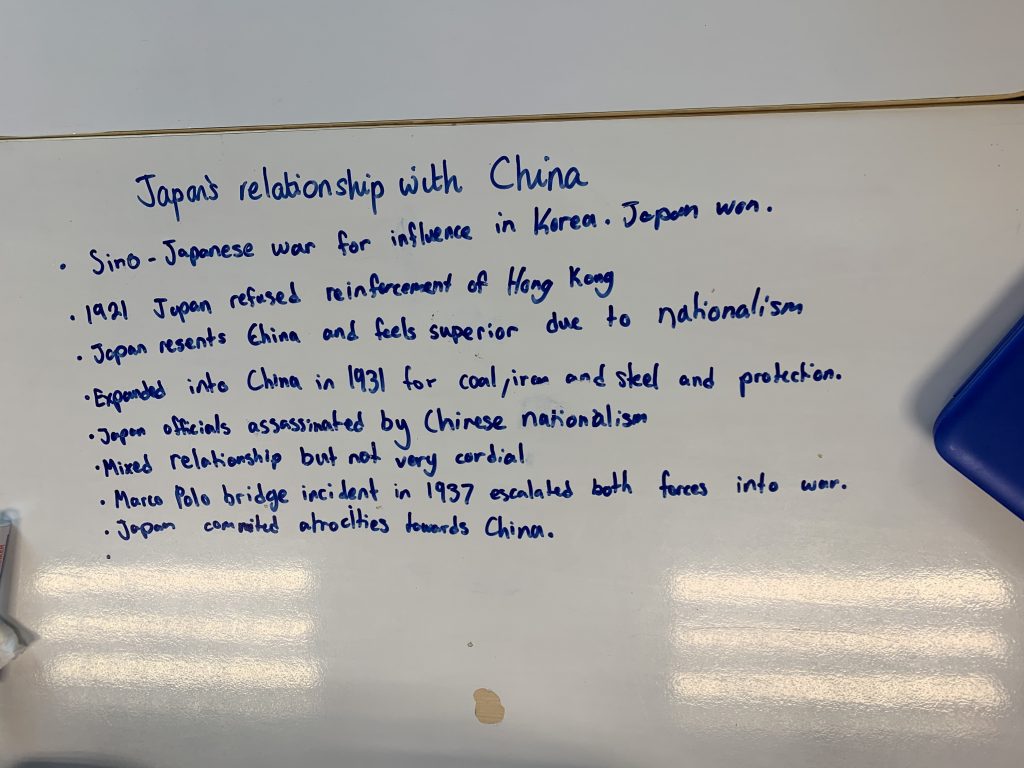

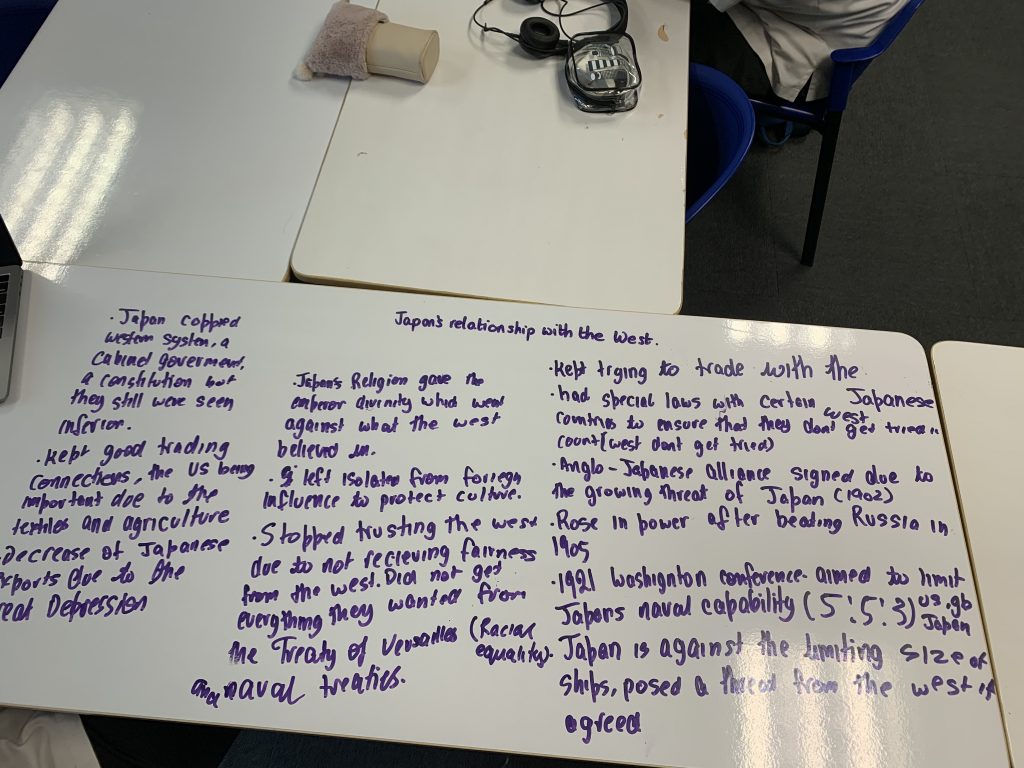

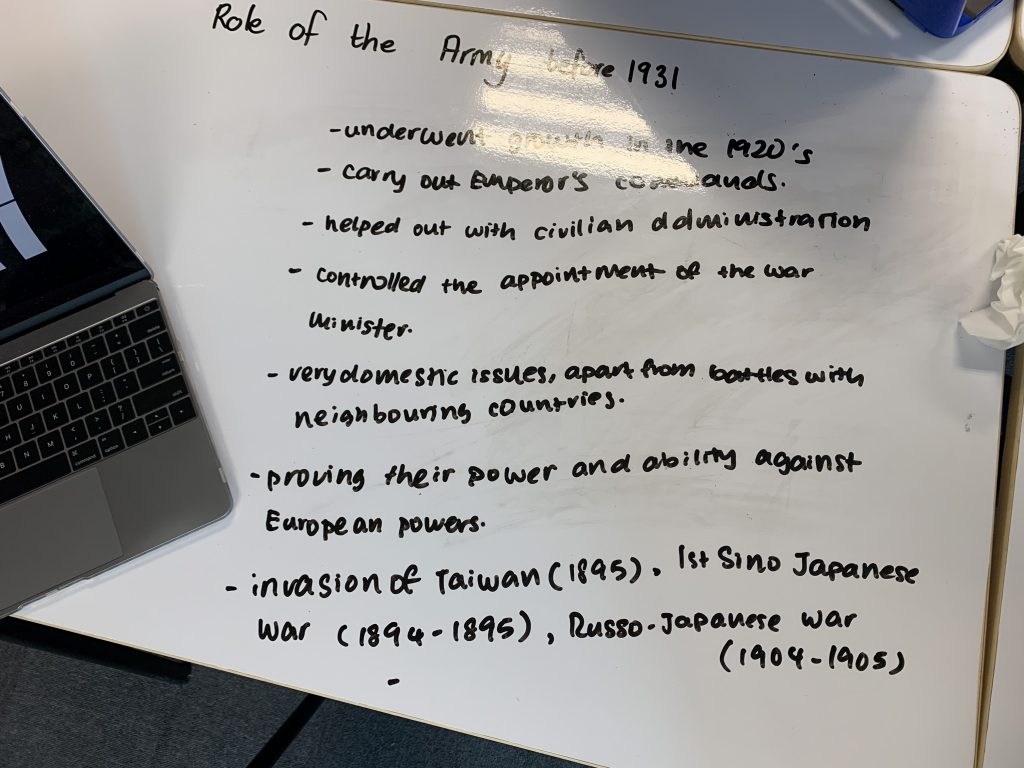

- Student Summaries

- Sources

- Why war against the West in Asia?

- Was there an alternative?

- Strategy

- Perspectives and Judgements

- Further Resources

Timeline 1839-1930

1839-42 First Opium War. It led to the Treaty of Nanjing, giving Britain Hong Kong and increased the number of treaty ports from one (Canton) to five.

1854 Commodore Perry first met with the Japanese (although Washington gave permission to do so in 1852). He had a substantial force for the meeting, even publicised to the world beforehand (Perry was determined not to be turned away). The Japanese government wanted to turn him away but knew they were outgunned.

1856-1860 Second Opium War. Britain took advantage of the Qing government’s problems with the Taiping Rebellion to further their trade. A protracted war resulted in GB taking Kowloon and gaining more trade advantages.

1859 By this year, all the major powers had access to Japanese markets and to the key ports. Some also had the law of extraterritoriality agreed upon, whereby foreigners could not be tried in Japanese courts, regardless of their crime.

1860 PM Naosuke assassinated because of his policy of compromising with foreigners.

1868 Meiji Restoration. This was a political and social revolution in Japan from 1866 to 1869 that ended the power of the Tokugawa shogunate and returned the Emperor to a central position in Japanese politics and culture. It is named for Mutsuhito, the Meiji Emperor, who served as the figurehead for the movement.

1871-73 Iwakura mission, government representatives sent to Europe to gather information.

1894-95 War with China. It was fought over the influence for the Korean peninsula, arguably started by the Japanese by fermenting dissent to Chinese influence. China responded but the ensuing Japanese victory was a surprise to all.

1902 Anglo-Japanese Alliance. This cemented Japan’s growing stature in the world. Britain signed it because of the growing threat of Japanese naval forces to its colonies in Asia and Russian expansionism.

1904-5 Russo-Japanese War. Japan proved itself to the world that it could rival the strongest powers.

1910 Japan annexed Korea, it was formerly a protectorate in 1905. She knew the West would not object.

1921 Japanese Communist Party, controlled by Comintern (USSR).

1921 Washington Conference. One aim was for the West to limit Japan’s naval capability. The ratio of 5:5:3 for US:GB:Japan was not well received at home. And a Four-Power Pact (France added) replaced the Anglo-Japanese alliance. However, she extracted concessions that Guam, Singapore and Hong Kong would not be reinforced.

1930 London Naval Treaty. Aimed to limit the size of all ships (Washington 1922 was for the larger only ). The Japanese Navy (modelled on the British Royal Navy) was against this as it would make it difficult to defend the Pacific from the West (especially the US). However, the government overruled this.

1839 to 1930

Watch the following documentary and answer the questions on the document below.

Documentary Questions – Part 1

First World War

Khan Academy – Japan in World War I

1914-18: Making Sense of the War (Japan)

- Japan entered the First World War in 1914 but it was not without disagreement.

- As Japan’s influence over South Manchuria was due to expire in 1923, it issued Twenty-One Demands in the hope of extending or even increasing the control it had. These were imperialist policies designed to take advantage of their military strength, Chinese weakness and Western preoccupation with the First World War.

Japanese Government, “Twenty-One Demands,” April 26, 1915

Group One of the Demands

Group Two

The article above ‘Making Sense of the War (Japan)‘ explains the following consequences of the First World War:

1. Acceptance of the concept of Total Mobilisation,

- The Munitions Industries Mobilization Act was set up in 1918, designed to manage the production of munitions and the conscription of workers.

2. And Japan now saw itself as a major player on the world stage.

Japan and the Russian Civil War

- The Russian Revolution took place in 1917 and the country soon afterwards descended into civil war. The Bolsheviks, under Lenin, took power and wanted to consolidate their rule across the country. Japan tried to take advantage of the country’s instability and establish a buffer state in Siberia.

- This event is also called the ‘Siberian Affair‘ and lasted from 1918 to 1922.

- Japanese losses were over several thousand and only antagonised the relationship with the Soviet Union.

Treaty of Versailles,

- The Treaty led to a Distrust of Foreigners. Despite the growing power of Japan, there was still a feeling that foreign powers did not see them as equals. They did not receive what they wanted from the Treaty of Versailles and the naval treaties did not seem fair either. Japan had copied Western systems, a cabinet-government, a constitution (modelled on France and Germany) and adopted their culture. It seemed that regardless of what they did, foreigners would always see them as inferior – at Versailles, Japan asked for a racial equality clause to be inserted…it was rejected. Even when the Japanese Communist Party was set up in 1921, the fact that it was controlled from Moscow only increased distrust of foreigners for some.

- Click on the link below for more content and analysis of the Treaty …

Taisho Democracy

(Gordon, A. p. 161)

- This was a period of time where Japan was moving towards becoming a strong, democratic state.

- Interestingly, it was also a term that was use after the event, generally in the 1950s and 60s.

- So what changed during this time? According to Ethan Segal, writing in Meiji and Taishō Japan: An Introductory Essay:

- Women became more active in public life, taking professional jobs, becoming writers and even moga or ‘modern girls’. These women had western liberal attitudes to fashion, sex and dating.

- It had become a founding member of the League of Nations in 1920.

- It had copied many of the western ideas and customs, from dress and food to transport and culture. Urban centres increased in size and a the country’s middle class grew.

- Japan became a constitutional monarchy. This brought the country respect.

- Universal education was adopted, this increased literacy in the country as well as a growth in publishing.

And from Andrew Gordon:

- More people took part in public life than ever before.

- In the teens (1911 to 1919), Japanese people demanded that governments consist of a prime minister and a cabinet comprised of elected parliamentary representatives. This was achieved by the mid-1920s. However, various governments were still criticised for cooperating with non-political elites (zaibatsu, the military).

But…

Opposition

- There was a Growing nationalism. Some in Japan were fearful of foreign influences, such as the changing culture and events in Asia such as the Opium Wars and their consequent unfair treaties. A Chinese phrase was used to describe this – ‘naiyu-gaikan’ or ‘troubles at home, dangers from abroad’. The country had been largely isolated from foreign influences for centuries to protect their culture so fear from abroad may be part of the Japanese psyche. A consequence of this feeling was the forming in the 1920s of ‘Patriotic Societies‘, nationalist groups which were popular with Army officers and responsible for moving the country to the Right.

- Resentment of China. Despite much of Japan’s culture being influenced by China, the growing nationalism and the military defeats it endured (1894-5 Sino-Japanese War) led to a dislike of the country and a belief that they were inferior.

- Cultural and conservative beliefs. The Japanese religion of Shintoism gave the emperor imperial divinity and Confucianism, obedience and a code of personal behaviour. This went against some of the beliefs and behaviour of the West.

- Economy. The manufacturing and export of silk drove the economy, agriculture and textiles were secondary to this. Exports to the US were especially important although China’s growing textile industry was becoming a threat to Japan’s economy. Furthermore, the catastrophic earthquake of 1923 hit Tokyo and Yokohama killing over 100 000 people and severely harming the economy as two huge industrial centres were ruined. As evidence of Japan’s developing racism towards others, 6000 Koreans were tortured and murdered by police after the earthquake. According to The Great Japan Earthquake of 1923,

- When you factor in the growing population, 35 million in 1873 to 60 million in 1925, economic concerns increasingly affected Japan’s desire for more natural resources and improved trade links. Even though capitalism had improved economic growth for the country, the inequality gap had grown, especially for the rural population. They could potentially be supporters of the Right in Japan.

- Rearmament. There was little in the 1920s! Read ‘Japan and the Russian Civil War’ above to work out why.

- However, as a consequence of foreign influence, distrust and growing nationalism in the 1930s, Japanese governments invested heavily in their armed forces. With each military success (China, Russia, WWI) the clamour to continue rearming was maintained.

- Manchuria. In the late-19th century and early 20th, Japan began to increasingly rely on the resources of Manchuria. It had moved forces into the region after the First Sino-Japanese War of 1894-95 and there they remained to maintain a Japanese influence. Ishiwari Kanji, military strategist and future general, argued that Manchuria should be fought over. However, this would only be the first war of many to come, leading to Japanese dominance in Asia. But in 1924 Chaing Kai-Shek became the Chinese nationalist leader (of the Kuomintang). He began campaigning in 1926 to take control of the Yangtse region and the north (threatening Japan’s control of Manchuria which was under Chang Tso-lin, who receptive to Japan). This was a huge problem for the government.

Road to War Documentary

This is very useful as it largely gives a Japanese perspective of how the Second World War began in Asia in 1941.

From the beginning to 21:00, you will look at the background of Japanese foreign policies up to and including the 1931 Manchurian Conflict.

a. Who did the Japanese professor blame for starting the Second World War in Asia?

b. Does the 1907 war plan to attack the US fleet mean that they were to blame for the Second World War in Asia?

c. Was war inevitable between Japan and the West?

d. Which Western country was a friend until the 1920s and who was not? Why?

e. What was Japan’s solution to their economic problems? Why?

f. What was the Japanese civilians’ experience of living in Manchuria?

From 21:00 to the end, you will see how the Japanese foreign policy became more aggressive.

g. What did the young Japanese think of their Asian neighbours?

h. How did the Japanese democratic government collapse?

i. Who was the only stable influence in Japan? Why?

j. Could the emperor have ruled Japan?

k. Which countries did Japan ‘join’ with in 1936? Why?

l. Why did Japan continue the expansion into China in 1937? What triggered the war?

m. What was the Western reaction to the Japanese attack on Shanghai?

n. How did Japan attack China?

o. What happened to the Japanese advance in China?

p. Why did the Japanese soldiers not surrender?

q. What was the impact of this on the Chinese civilians and prisoners?

r. What was the US reaction towards the Second Sino-Japanese War?

s. What was the economic impact of the war in China?

t. How strong were the Japanese armed forces?

u. Who impressed Japan and what was the consequence of this?

v. Which countries had the resources that Japan needed?

w. What was the US response to the Japanese occupation of French Indochina?

x. What were the two options for Japan?

y. Did the US know about the attack on Pearl Harbor?

z. Was the attack on Pearl Harbor a success?

Was the Taisho Democracy a Success?

Yes:

- A commoner, Hara Takashi, was appointed Prime Minister in 1918

- The Japanese Diet had two houses and the House of Representatives was directly elected by the people.

- Party politics flourished at this time with a wide range of political parties that represented all elements of society.

- Japan was becoming a key player in international relations, for example the League of Nations and Washington Conference.

- In 1925 universal male suffrage was granted and the electorate increased from 3 million to 14 million.

No:

- Women did not get the vote

- Failed assassination of Hirohito in 1923

- Economic problems existed throughout the period: both and inflation and debt were evident at the close of the First World War.

- The assassination of Prime Minister Hara in 1921 led to some instability.

- Changes to the political structure were banned by the Peace Preservation Law.

- There was suppression of the Communists.

- Politicians were perceived to be corrupt and with little interest in the peasantry and workers.

- The inability of Taisho politicians to deal with effects of the Great Depression (1929) also undermined the Democracy.

- The emperor still had huge power over the people. For example,

(Gordon, A. p. 165)

- He was also the supreme commander of the military, this allowed some to act independently of the prime minister.

1931-37

- The beginning of the decade gave two choices to Japan: to join with China to take Asia forward and change the balance of power OR to protect a weak China from the West by occupying it and making use of their resources to build a strong Japan. The government became increasingly influenced by the military and the second option became policy.

- The Great Depression (huge unemployment across the world, economies declined, protectionism grew) was clearly a factor in this decision (although the US and Germany were affected much more than Japan). It led to a decrease in Japanese exports (1 billion yen between 1929 and 1931), with the textile trade (silk) and farmers especially suffering the most. Rural poverty rose as a result. The devaluation of the yen increased exports but the Depression led to increased imports.

- In 1931 PM Hamaguchi Yuko was assassinated, killed by a nationalist. He was succeeded by a similarly thinking Hashimoto Sakurakai. This led to a failed coup by the nationalists; their leaders only given lenient sentences because of their patriotic beliefs.

- Itagaki Seishiro and Ishiwara Kanji (two staff officers in the Kwantung Army) were anxious about the effects of the global depression, in particular, it reduced the profits of the South Manchurian Railway. A collapse of the company would severely affect Japan’s ability to acquire the resources it needed. Morever, some in Japan believed that it was becoming overpopulated and felt that Manchuria’s ample space would provide the solution.

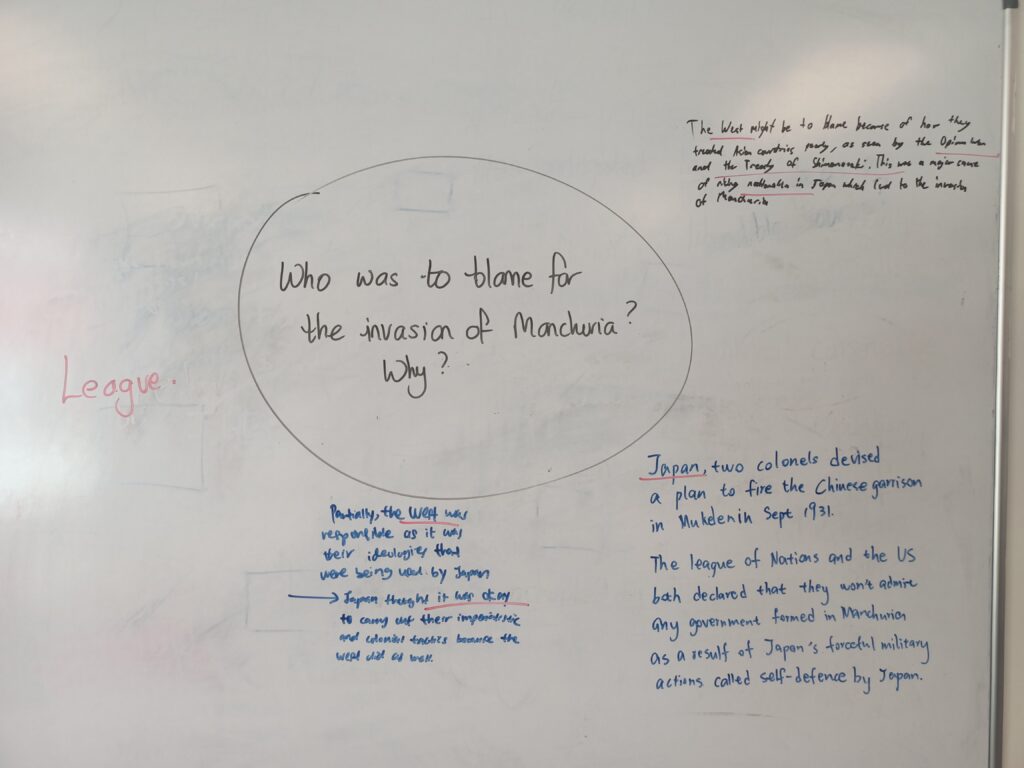

Manchuria and the Mukden Incident, 1931.

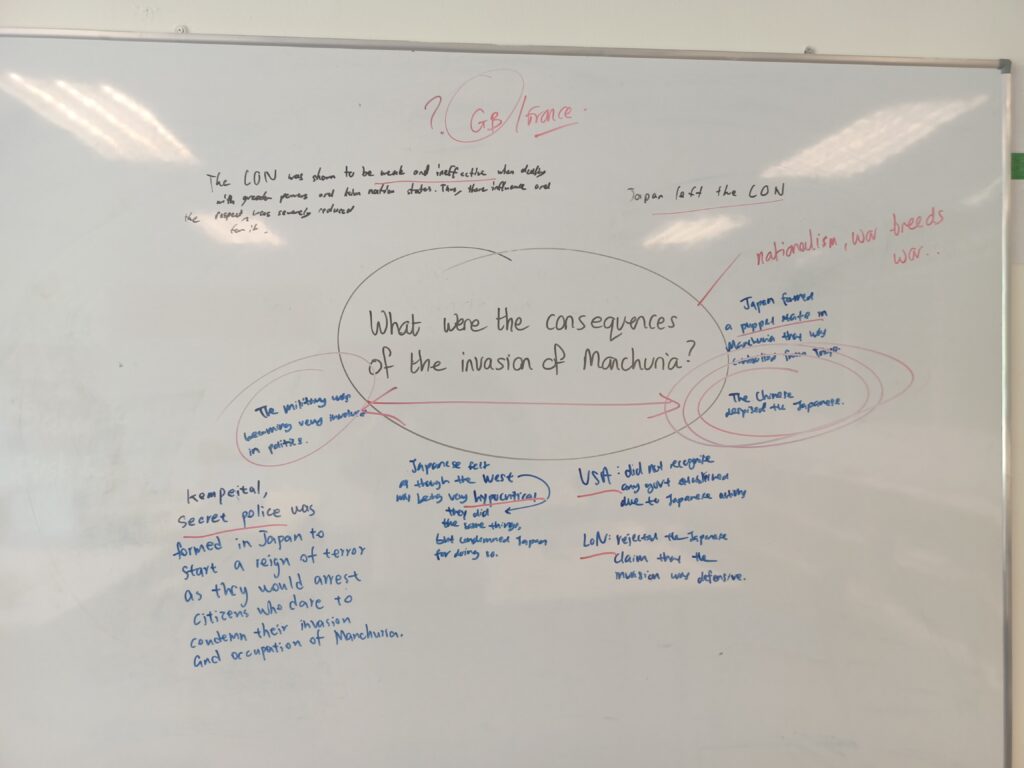

- The Kwantung Army took the initiative and arranged a bomb to explode on the railway. The government knew about it beforehand and sent a messenger to prevent it, however, he was involved too and only went ‘slowly’ so as to give time for the plot to succeed. Soldiers were sent into southern Manchuria, (troops had been in China since the Boxer Rebellion and those from Korea were also involved). The war spread to southern China even into 1932 (to Shanghai and Nanking).

- A puppet was installed, previous Manchu emperor Pu Yi, (also in Korea) in ‘Manchukuo’.

- The League of Nations sent Lord Lytton to find a solution. Japan’s argument was that the situation was merely Chinese internal problems and they were protecting Japanese business interests there. However, the League ruled against them and this ultimately led to their withdrawal. Why would a Western-led organisation rule against them for imperialist policies that they themselves were still maintaining? The decision only reaffirmed their belief in inequality and prejudice against Asian people.

Japan and the Manchuria Crisis

1931-36

- Importantly, the actions of the Kwantung Army were decided independent of Tokyo. This was to be a factor in Japanese affairs for the 1930s and the Second World War. Moreover, the constitution made the emperor commander in chief and in charge of the armed forces, not the government.

Strategy

- The army officer-class system was meritocratic and extremely rigorous. The best graduates from their staff college were chosen to observe the Entente armies of the First World War. Their key observation was that Japan must be able to wage total war. These officers ensured that they take senior positions in personnel departments of the armed forces so that they could promote like-minded individuals. This took time but by the 1930s, this total-war ideology was the belief of most of the officers in the Japanese Army.

- They also believed in the Cannae strategy, whereby the army surrounds the enemy quickly before destroying it. Staff officers studied the Eastern Front of the First World War, where Germany quickly destroyed large Russian armies in short campaigns. The emphasis was on the latter as they knew the economy and their lack of natural resources would hinder a long war.

- An important figure from this period was Kanji Ishiwara.

- He was a brilliant, if not arrogant, staff officer who played a key role in the successful mobile warfare strategy in Manchuria. He believed that there would eventually be a clash of civilisations between the East and West (probably the United States). He also saw that Japan had only planned for a short war (see Taisho Democracy: Rearmament). To be able to fight a protracted war, Japan needed the economic resources of China and Manchuria. If all three were ‘united’, a large-scale rearmament programme would be possible and the clash against the West would be successful.

- This was close to the eventual strategy of the Army, they wanted to take the resources of Manchuria to ready the country for war against the Soviet Union. On the other hand, the Navy wanted to aim south and take on the European imperial powers and the United States. This would leave Japan as the most powerful country in Asia.

- Clearly, this meant that resources were not focused on one strategic objective. It also meant that there was friction between the two services and even conflict with the government. The February 26 Incident was a coup involving 1400 army officers…

- There were two groups or strategies within the Japanese Army: the Koda-ha or Imperial Way faction OR the Tosei-ha or Control faction. Both wanted an imperialist policy but each had their own way to achieve it.

- The Imperial Way was more radical, preferring to establish a totalitarian and militaristic government. The Control faction preferred to cooperate with Japanese industry and members of the parliament (diet) to determine national policy.

- Several key ministers were killed (including Korekiyo) although it was ultimately unsuccessful, Ishiwara putting it down. This increased his influence over the direction of the army too. The defeat of the Imperial Way meant that the Control Faction was dominant. However, some of the ideas of the Imperial Way remained influential in the government.

- However, despite launching a five-year plan for rearmament, he was transferred to Manchuria as his senior officers did not want a major-colonel leading the army and he fell out with General Tojo, arguably one of the men who took Japan to war in 1937 and 1941.

Political Japan

- 1931: Political assassinations and the failed coup prevented a strong government. Even when a coup succeeded, lenient sentences were handed out. BUT 1936 – the Young Officers’ coup, the murder of the PM’s brother-in-law. It failed and thirteen were executed, many were also demoted if a lesser involvement.

- During this time, the Left were arrested suppressed. 1925: Peace Preservation Law gave the police more powers to arrest anybody guilty of overthrowing the government. In 1928, the police rounded up thousands of communists, a year later thousands of anti-government supporters. By 1945, 75 000 people had been arrested under this law.

- Takahashi Korekiyo (finance minister 1931-36) was responsible for taking Japan out of the Depression. He abandoned the gold standard to reduce the value of the yen and increase exports. Government monies went into agriculture (it grew slightly) and other industries (chemicals, ship-building, metals – which all did well in terms of production). Military spending increased (it rose from 9% GNP from 1933-37 to 38% from 1938-42) and this influenced other industries. However, as Korekiyo was assassinated in 1936, a key figure who could have eventually restrained military spending, was gone. Then the military put forward a five-year plan to produce more iron, steel, oil, electrical power etc. Importantly, to help with a possible ‘total war’, in 1938 the National Mobilisation Law gave the government (military) more power over the economy and country to control labour and materials.

- Furthermore in 1936, Prime Minister Hirota Koki , arguably in hindsight, made an error in ensuring that all ministers had to be serving officers. This made the military extremely powerful in the government.

- Japan’s militarism was in part was copied from Germany, especially in the form of education for their youth. Yoichi Kiuchi, in the article ‘Unrequited Love for Germany’, he argues that Japan borrowed educational ideas from the US and UK in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Why War in China?

- Two reasons for building on the 1931 expansion into China: secure itself from the threat of Jiang Jieshi AND a small advance in NE China would bring much-needed coal, iron and steel.

- According to Dr. Edward Drea, Japan was fearful of the growing power of the Soviet Union, whose armed forces had just recently surpassed those of her own. For this reason, the Army wanted to invade China (despite the danger of a protracted war) for it to be a buffer against future attack.

- 1936: Fundamentals of National Policy – this contained the features of the New Order and Co-Prosperity Sphere. These included the elimination of tyrannical leaders in Asia. And to build a strong coalition of Japan, China and Manchukuo. Northern China would be a special region because of the economic significance and SE Asia would be gained peacefully in time.

- The trigger was 1937 Marco Polo Bridge. It did not immediately lead to war but Japanese forces began to arrive on mass. By the end of the year, 200 000 soldiers were in the field. Once the fighting had begun, Tokyo had no power to stop it. The military had decided policy once again.

- The war began with successes for Japan but the Guomindang did not surrender. As the European war began in 1939, France and GB were in no position to stop Japan and allowed access through their colonies. Moreover, the actions of the soldiers in Nanking (the Rape of Nanking) shocked the world and could have been a factor in failed diplomatic efforts with the West prior to Pearl Harbor. Indeed, Japanese actions against China had persuaded some in Roosevelt’s Cabinet (US Ambassador to Japan, Joseph Grew was one).

Student Summaries

Sources

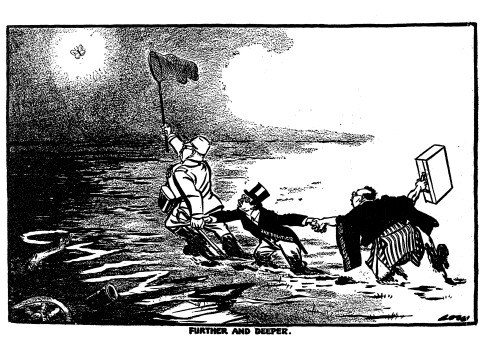

This source is a political cartoon titled “Further and Deeper” and was published in the UK newspaper The Evening Standard on January 19, 1938

From https://www.thinkib.net/history/page/20454/3-japanese-expansion-in-east-asia-1931-1941-atl

Why War against the West in Asia?

After Europe became embroiled in war in 1939, it was clear to Tokyo that European colonies were defenceless. Their strategy was then to either strike south to SE Asia or north to acquire East Asia (antagonising Russia into a possible conflict). Tokyo could not decide.

According to Richard Overy, the Japanese were also fearful of being isolated.

The war in Europe brought strategic advantages for Japan but economically it made it difficult. The demand for oil rose, as it had for tungsten, iron, tin, rubber, etc. SE Asia could supply many of these and Indonesia oil. The USA was also a possible source of supply.

Japan first pressed France for access into SE Asia, it gave way easily. But the Dutch were more stubborn over Indonesia. Their continuing war in China brought sanctions against it from the Dutch and the USA (July 1941). Relations with the West had deteriorated because of the Japanese alliance with Germany and the US policy of supplying arms to China. The US was concerned about her own interests in the region (Philippines) so acted to limit the power of Japan.

The 1 Reason Imperial Japan Attacked Pearl Harbor: Oil

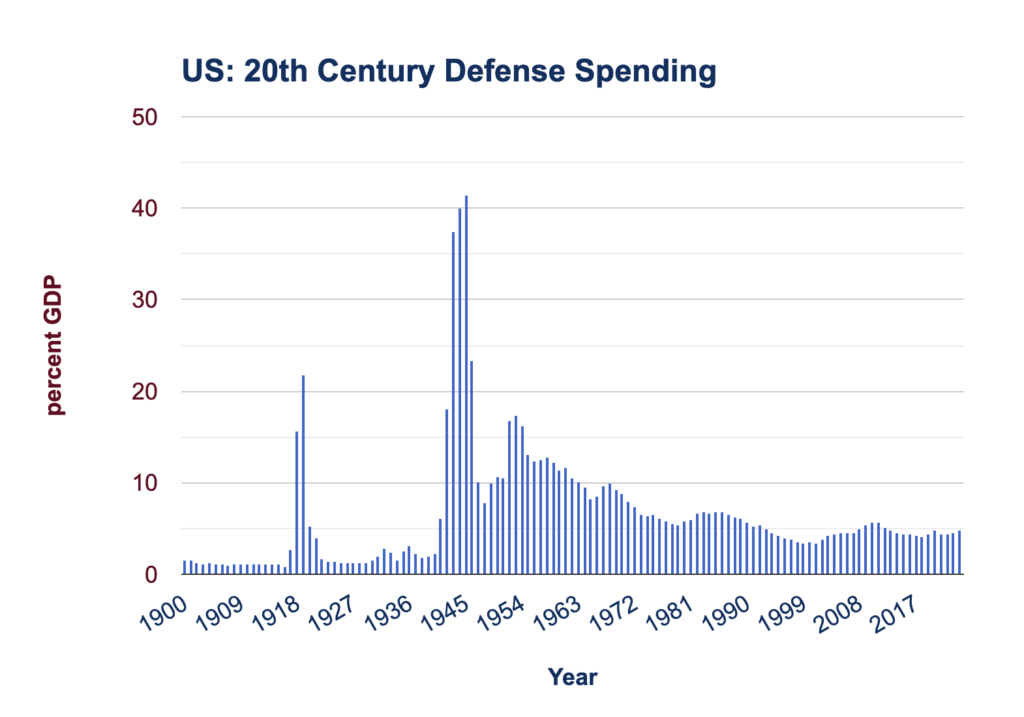

Japan had to make a decision for war quickly as time was running out. It knew that most of the US military was weak but their navy was growing at a rapid rate during the 1930s. The longer Japan waited, the less chance it had to defeat the US. The graph below shows how little the US were spending on defence, just over 1% of GDP for the 1920s and rising to between 2 and 3% for the 1930s. 1941 saw a rise to over 6% and this may have been a factor in Japan attacking Pearl Harbor.

It did so but the civilians in the government disagreed. It continued to use diplomacy to acquire the oil embargo to be lifted for example but to no avail. The argument for the south became the preferred policy because of the Japanese failure at the Battle of Khalkin-Gol in 1939 (arguably, this also had an influence on Japan’s refusal to declare war on the USSR after the invasion by Germany in June 1941. It turned down the German request to go to war and preferred to remain neutral). Furthermore, after nearly a decade of war, the Cabinet was dominated by military appointments. Although the navy was less aggressive than the army, the latter won through, arguably their ‘Bushido’ culture affecting their decision-making.

There were several ‘hawks’ in the Japanese Cabinet, none more so than Yōsuke Matsuoka, the foreign minister. He purged his ministry of any supporter of either the US or the UK, and was instrumental in signing the Tripartite Alliance with Italy and Germany. Another was Hideki Tojo, Prime Minister in 1941-44. He argued strongly for a war against the US to reduce the Western influence in Asia.

Finally, arguably the most important individual was Admiral Yanamoto. It was his opinion to go to war that swayed the Cabinet to support the policy. He was not sure himself about war with the US (he had served as a naval attache in Washington and understood their defence capabilities) but if there was to be a conflict, he wanted to lead it. Consequently, for the attack against Pearl Harbor, he was the man to plan and execute it.

The decision to attack the US was taken in July and August 1941 although planning had begun in January. The occupation of southern Indochina and the US oil embargo had both influenced the decision. They established the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere (first mentioned in 1940) at this time, their ambitions clear as the area included many Western colonies.

Was there an alternative?

Japan did pursue diplomatic avenues but not enough. Indeed, their Ambassador to the US, Admiral Nomura, met representatives of Roosevelt’s administration throughout 1941, but the military dominated the policy-making. Furthermore, even when Prime Minister Konoye tried to negotiate with the US after August, the army and Imperial Council gave him both a tight deadline to succeed and demands which were likely to be rejected.

The Japanese government was not a dictatorship like Germany and Italy. Their respective leaders had vast amounts of power and took their countries to war. Emperor Hirohito was the spiritual leader of Japan and the commander of the armed forces. Had he intervened in the plans to create the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, or objected to them, war with the West could have been averted.

Tokyo could have pursued only the possessions of European states. They could have reached a deal with Washington that the Philippines and Hawaii were not territorial ambitions of theirs. But the Japanese clearly thought that the US would enter the war regardless.

Strategy

Pearl Harbor was attacked December 7 1941, Hong Kong surrendered Christmas Day, Manila, Kuala Lumpur and Singapore in January 1942. Indonesia was taken in March. The decision to attack Pearl Harbor was justified in the name of defence. If Japan did not act soon, the US would cut off their access to the raw materials they needed. The initial strategy was to attack the only force capable of stopping a future operation for the Philippines and the Indies – the US Navy at Pearl Harbor. If the operation was undertaken first, Japan itself would be vulnerable to a US attack as their forces would be indisposed in their southern offensives.

Japan, or Admiral Yamamoto, judged that the war against the US should be swift. If it was fought for longer than two years, it could not win. Therefore, a huge knockout blow, via a surprise attack, was planned. It would be so devastating that America could not recover for years. To read more about the Japanese strategy and the war in Asia, go to this page.

Perspectives and Judgements

The Pacific Campaign by Dan van der Vat, argues that the war was brought about by the blind obedience of the Japanese people to the generals and admirals and those who supported them.

Q. How much was the West to blame for Japan’s growing nationalism?

From Japan’s perspective, the West was both hypocritical and aggressive during the 1930s. It pursued imperialist policies around the world but did not ‘allow’ Japan to do the same thing. In restricting her access to important raw materials, this was an aggressive measure aimed at protecting their own colonial interests. Furthermore, perhaps Washington did not give Japan much room for manoeuvre. Attempting to limit their actions in Asia could only provoke a military response.

On the other hand, Japan could have pursued a less aggressive strategy with the West. It signed a Tripartite Act with Germany and Italy in September 1940 (it had hoped it would deter the US from aggressive action) and continued both the occupation of Indochina and war with China. Furthermore, the military-dominated cabinet and only added to the nationalism of the country.

Q. Why did Japan go to war in 1941?

It boxed itself into war because of a military-led government, arrogance that it could defeat several western powers at the same time and fear of being surrounded by ‘imperialists’ who threatened their political and economic security.

Further Resources

There are many documentaries and movies on the topic of Japan and the Second World War. Some are very good and others just for fun (or bad!). The movie Pearl Harbor is one of the latter…https://youtu.be/W761PvY7B4w

A better movie is Tora Tora Tora.https://youtu.be/-n1pKsGqrqQ

For documentaries, watch the following,

The documentaries below are part of an excellent history series entitled ‘World at War’. It was made in the 1970s and contains many interviews with people who took an active or leadership role in the Second World War.

The Word at War Episode 6 – Banzai, 1931-42

The World At War Episode 7 HD – On Our Way: U.S.A. (1939–1942)

The World at War: Episode 14 – It’s a Lovely Day Tomorrow: Burma – 1942-1944 (14 of 26)

The World At War Episode 22 HD – Japan (1941–1945)

The World At War Episode 24 HD – The Bomb (February – September 1945)