- General Resources

- Early Political Crises

- Political Parties of the Weimar Republic

- Political Constitution

- Social and Economic Policies

- Was it a Golden Age?

- Foreign Policy and Rearmament

- Bruning’s Chancellorship: The Beginning of Authoritarian Rule?

- Why did people who lived during the Weimar Republic begin to vote for Hitler?

- Historiography

1. General Resources

2. Early Political Crises

Bavarian Soviet Republic, 1918 to 1919.

German sailors mutinied at the port of Kiel in October 1918. They then set up councils or Räterepublik (based on the Russian Soviets) where workers had power; this ‘revolution’ spread across the country. This was an immediate threat to the new Weimar Republic, led by President Ebert.

Kurt Eisner, the leader of the Independent Socialist Party, called for a general strike in Bavaria. He led a large crowd into the local parliament building, where he made a speech and declared Bavaria a Socialist Republic. Eisner made it clear that this revolution was different from the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia and announced that all private property would be protected by the new government. However, this government began to lose support as the economic conditions were deteriorating. This despite Eisner establishing a coalition with the Social Democrat Party.

Eisner was assassinated by a nationalist in 1919 but other socialist leaders and communists were able to continue the revolution, despite some disagreeing on how left and radical it should be. The Soviet was eventually led by actual Soviets so the Bavarian Prime Minister Hoffman asked for volunteers to fight the ‘foreigners’. The Freikorps, including the future of the SA, Ernst Rohm, and government troops answered the call and soon put an end to the Bavarian revolution.

The failed Soviet turned the people of Bavaria against the Left and may explain why the roots of the NSDAP were in Munich, the capital city of the state. However, arguably Bavaria was already a conservative state.

The new Ebert government had used the paramilitary Freikorps to put down left-wing councils in Germany. This may have given them some legitimacy and the rise of nationalism but at the very least it maintained the democratic government in power. Do the ends justify the means? Ebert also used the army although one could argue that these forces were independent of the government. The new president made a deal with the German Army under General Groener that he would leave the force alone as long as it supported the Weimar Republic. Groener accepted, arguably both strengthening the new government but also weakening it.

Spartacist Revolt, 1919

Why the Spartacists?

3. Political Parties of the Weimar Republic

German National People’s Party (DNVP) – Nationalist, initially opposed the Weimar constitution and the new political system. It called for the restoration of the monarchy and an authoritarian government. Supported by the middle and upper classes.

German People’s Party (DVP) – Began as a nationalist, conservative, pro-industrialist and anti-socialist party that was largely dismissive of the Republic. During the 1920s, it became more moderate, establishing good relations with centrist parties. Gustav Stresemann was their leader. Supported by business.

German Democratic Party (DDP) – Largely Protestant, middle-class, often from professional groups of lawyers, doctors and liberal academics. Firmly supportive of the Weimar Republic and resistant to militarism and antisemitism.

Communist Party (KPD) – Its earliest members came from the ranks of the radical Spartacist group. Drawing on a membership of more radical workers and a small group of radical intellectuals, the party was fundamentally opposed to the existence of the Weimar Republic

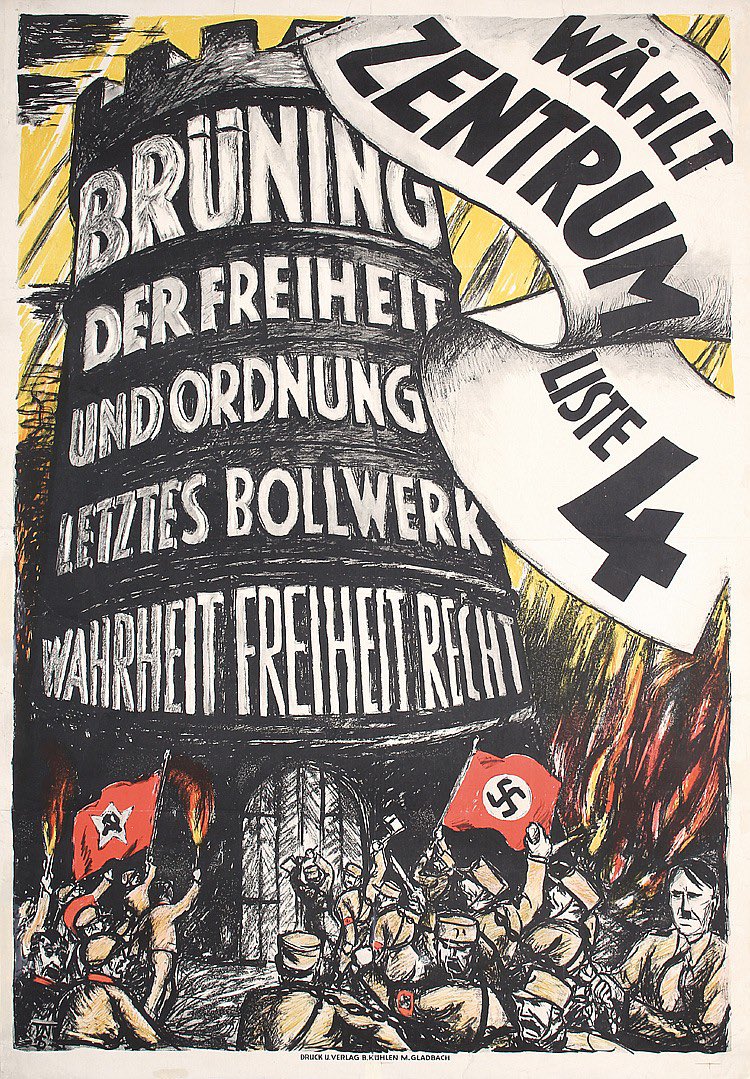

Catholic Centre Party (Z or Zentrum) – Was more diverse than any of its Weimar rivals. Catholic women voted for the party in very high numbers. The Centre Party was vital to the stability of the Republic, and it was a part of every Weimar government. Its leaders served as chancellors for nine administrations and were included in each of the twenty-one cabinets that ruled during the fourteen years of the Republic. With the change in leadership of the party in 1928, it drifted towards its more conservative wing which had evolved into the Bavarian People’s Party (BVP).

Social Democratic Party (SPD) – The SPD was committed to further reform of Weimar society and hoped to eventually make the institutions and economy of Weimar more egalitarian. Took its support from blue-collar trade union skilled workers, and at times from more progressive white-collar workers and intellectuals. German women from working class families voted for the Social Democratic Party in large numbers.

Bavarian People’s Party (BVP) – The Bavarian section of the Centre Party. More Conservative than its parent party. It was firmly pro-Catholic, anti-socialist and focused on interests specific to Bavaria.

National Socialist German Workers Party (NSDAP-Nazi) – Initially attracted young men who had been in the military and had not been able to reintegrate themselves into the civilian society and economy. The party also drew support from members of the lower middle class, shopkeepers, artisans and white-collar workers. Opposed to the Weimar Republic and continued to work towards its abolition even when they fought in elections from 1925 onwards.

Political Parties of the Weimar Republic

It is important to acknowledge that the elections above had a high voter turnout, usually between 75% to 79%. Arguably, this is evidence that the German people wanted democracy and were supportive, despite the difficulties and threats the Republic faced. Furthermore, more established democracies such as Britain and France had similar election turnouts.

4. Political Constitution

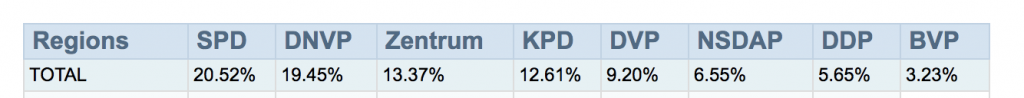

One could argue that the voting system in the Weimar Republic, proportional representation, was to blame for the political instability. Too often, parties which did not agree with the new republic became part of the government. For example, the 1924 elections produced the following results,

The table above shows that the DDP, Zentrum, DVP, BVP and DNVP formed the coalition in January 1925. Two of these parties were hostile to the Weimar Republic, the DVP and DNVP.

However, to counter this argument you can state that both of these parties took part in democratic elections and did not use violent methods to subvert the government or system.

Excerpts from the Constitution

5. Social and Economic Policies

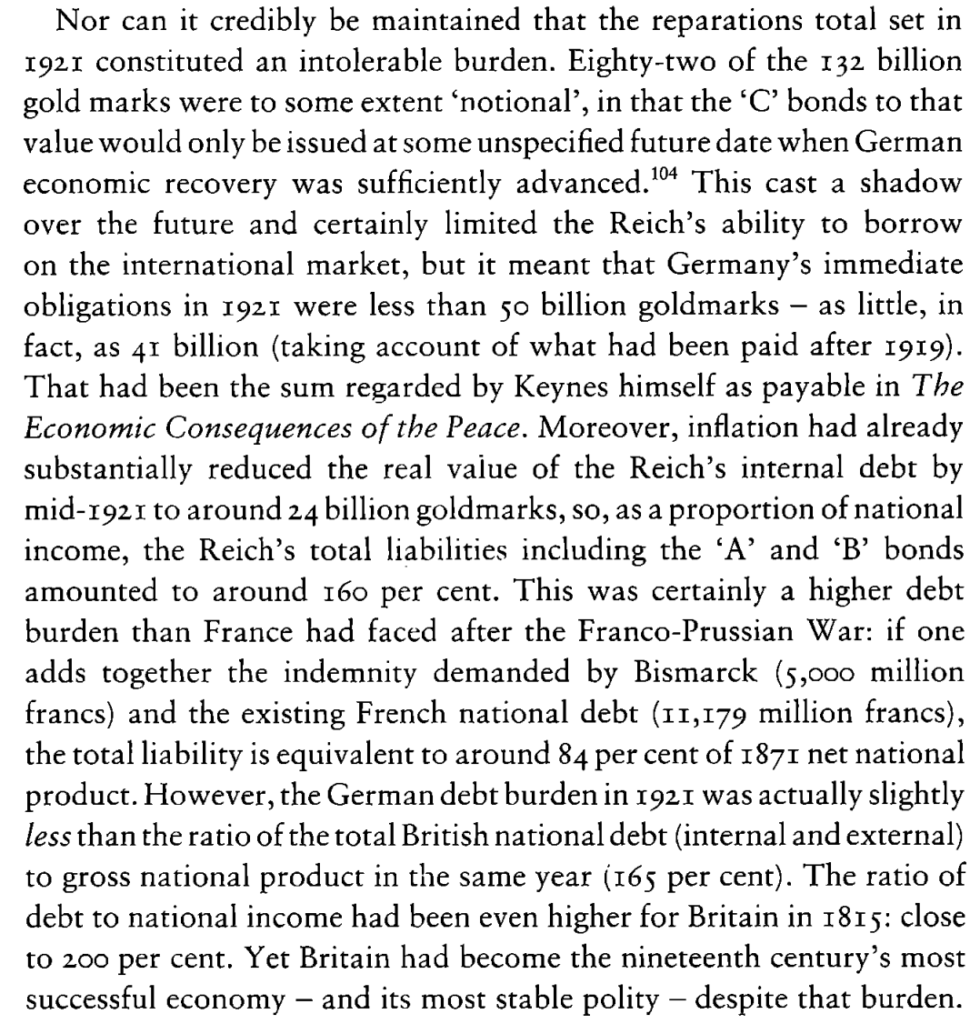

Could the new Weimar government afford the reparations? According to Niall Ferguson, they could. Read below to see this argument.

Unemployment and Inflation in the Weimar Republic

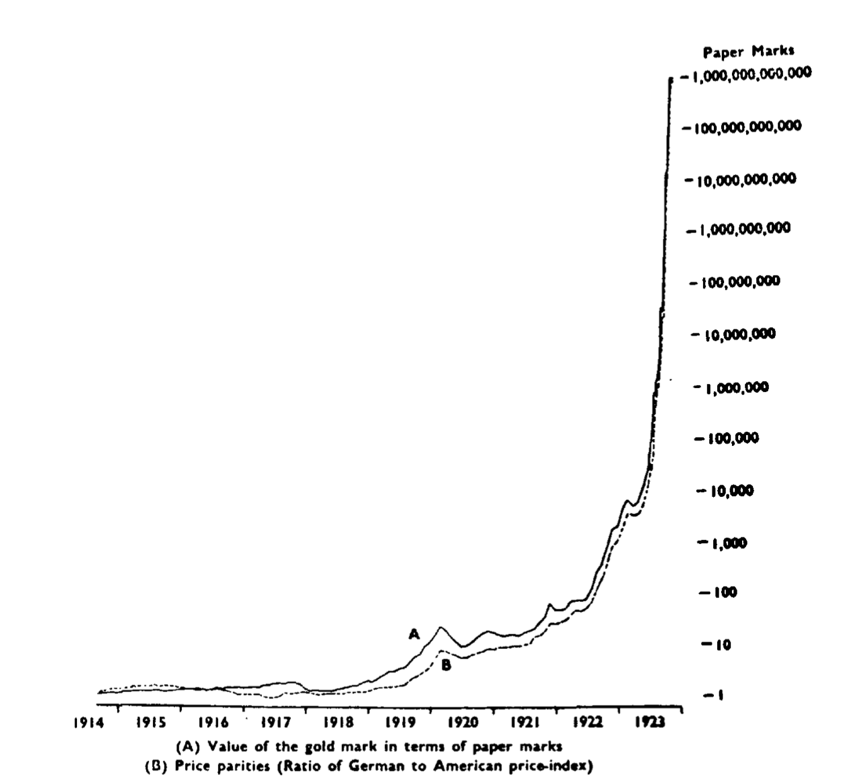

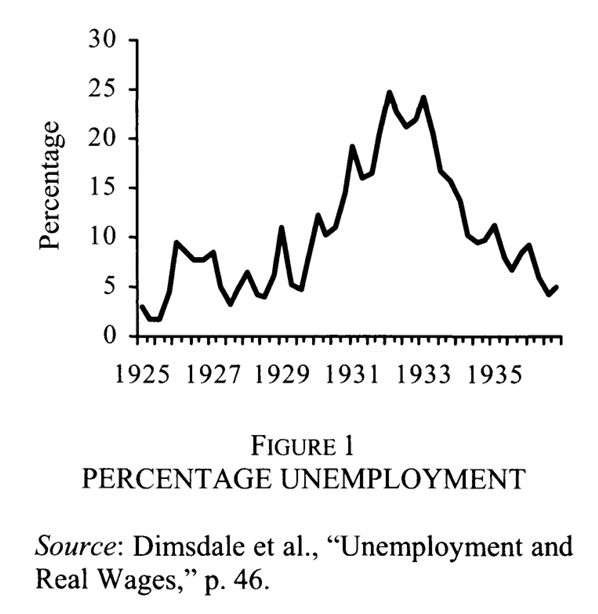

One of the arguments why the Nazis achieved power was because of the failure of the Weimar government to deal with the consequences of the Depression. Chancellor Bruning introduced austerity policies because he feared a repeat of 1923. However, one impact of this was deflation. This can be just as worse for the economy than inflation; a brief analysis is given here.

Inflation-growth-and-key-interest-rates-Germany-1926-1933

BBC: Weimar Germany, 1924-1929

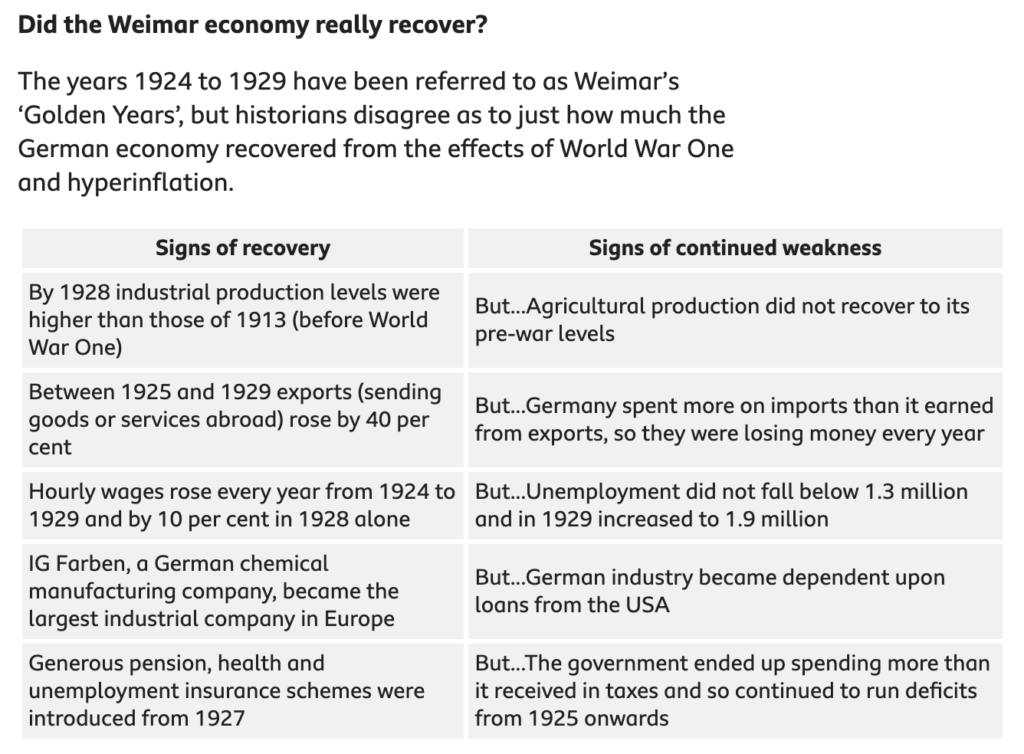

But…

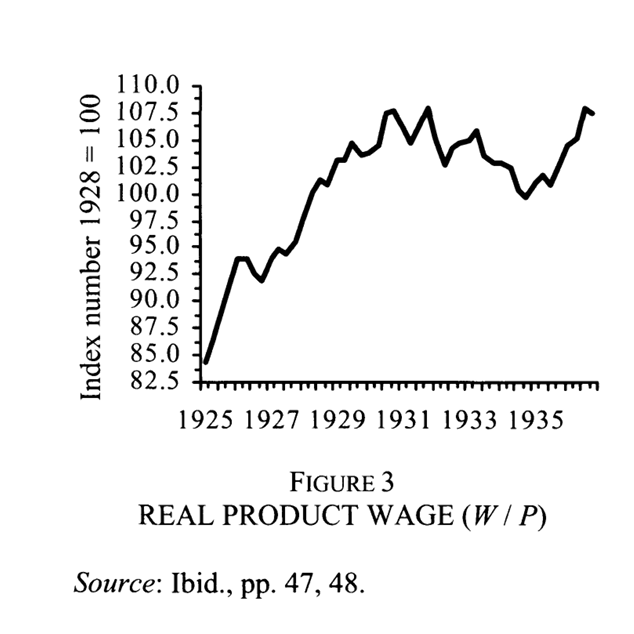

Wages

The Great Depression

- Share prices shortly after the Wall Street Crash tumbled across the world, over one-third in Canada and 16% in Germany. International trade then became severely affected, with real wages and industrial production declining and unemployment increasing.

- As a result of the hyperinflation of the 1920s, the Weimar Republic did not want to risk injecting money into the economy (through massive borrowing or printing off more money) to solve the problems of the Great Depression. Instead it chose to concentrate on austerity measures and a tight control of monetary policy. These were the policies of the Bruning government, which had been criticised for decades afterwards, people blaming them for the rise of the Nazis. Only in the late 1970s did his policies receive some balance, the Weimar economy arguably too weak before 1930 to easily solve the Depression problems.

- Perhaps a key reason why Bruning was criticised was because other countries such as the US adopted Keynesian economic policies under Roosevelt from 1932 (the New Deal).

6. Was it a Golden Age?

Weimar Republic and Stresemann

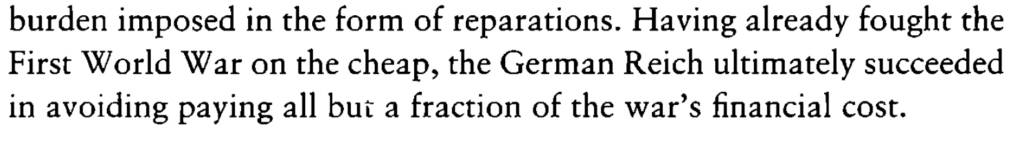

Hyperinflation and why Germany never really recovered from WWI

7. Foreign Policy and Rearmament

Disarmament and Clandestine Rearmament Under the Weimar Republic

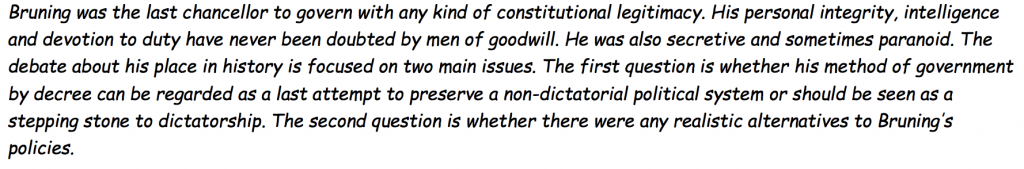

8. Bruning’s Chancellorship: The Beginning of Authoritarian Rule?

- Bruning arranged the suspension of reparation payments in 1931 as a result of the dire state of the German economy.

- He advocated austerity policies to solve the economic problems although the Reichstag would not pass them so he chose to use Article 48 to do so.

- When the NSDAP and KPD increased their seats in the 1932 election, he found it even more difficult to pass legislation. Article 48 was again the solution.

- In addition to austerity, he attempted to reverse the social and economic policies of previous governments; this would cut back on public expenditure. He also added tax increases and cut the salaries of government workers. This significantly reduced government borrowing.

How accurate is this poster for Heinrich Bruning and the German Centre Party, 1932?

‘Bruning, the last bulwark of freedom and order. Truth, Freedom, Justice.’

9. Why did people who lived during the Weimar Republic begin to vote for Hitler?

How did Hitler rise to power? – Alex Gendler and Anthony Hazard

- The Munich Putsch gave him publicity.

- Hitler played on the fears of nationalists about the Treaty of Versailles, the loss of the First World War and the poor state of the economy.

- Passionate speaker, also entertaining.

- Gave solutions, however impractical, to some of the people’s problems.

10. Historiography

Historian Says Weimar Republic Holds Potent Lessons for Today – Eric D. Weitz

Eric D. Weitz, “Weimar Germany: Promise and Tragedy

Richard Evans argues that a study of democracy is very relevant today. He explains that, according to the UN, the number of countries with strong democracies has decreased in the last few years. He asks is there are any parallels to the Weimar Republic and to what extent people should be concerned.

The Weimar Republic was a change from the Kaiser’s previously autocratic state. His regime was overturned in 1918 by a largely bloodless revolution, blaming it for defeat in the First World War and the problems it caused Germany. The new government was seen as the most democratic in the world at that time. Free elections, voting rights for both men and women, a free judiciary and press, local autonomy for states, etc. And democratic parties won a majority in the elections of 1919. So why did it fail?

Evans explains that the left and right would not work with each other. The two extremes did not believe in the democratic system of government that Germany had. Moreover, the poor state of the economy throughout the 1920s and 1930s continually maintained the opposition to it. Nationalism had not died from pre-war Germany and arguably grew up to as the 1920s ran into the 1930s. There was a belief that a return to better times was a viable option (the Weimar culture emulating the ‘Roaring Twenties’ was seen by conservatives as a step too far). Germany could be ‘great again’.

The nationalists were not united in the 1920s but their policies had similarities. Some advocated war as a solution to the country’s problems, and violence or intimidation were options to stop any opposition. This was carried out by paramilitary forces, the Sturmabteilung or Storm Detachment (SA) was one such group which were loyal to the Nazis. Ironically, Hitler came to power to stop the violence on the streets, much of which the SA had caused.

On the other hand, the Weimar Republic caused its own destruction. One can argue that Proportional Representation was a factor in bringing down the republic, Germany had fifteen different governments in as many years as parties were unable to reach a consensus. They were made up of coalitions and were liable to break down when events made life difficult for the parties. Richard Evans argues that this was not a factor, however. There were too many divisions before 1919 that it would always be difficult to reach consensus: left v right, communist v nationalist, protestant v catholic, wealthy v poor, rural v urban, state v state.

If you are to argue the Weimar Republic was always going to fail, Evans explains that the government had successes as long as the ministers were kept in post for many years. Gustav Stresemann was the foreign minister for nine successive Cabinets, Heinrich Brauns was labour minister for twelve and Otto Gessler was army minister for thirteen. These were all successful ministries.

But the infamous Article 48 was clearly a factor in bringing down the government eventually. The President could rule the country by decree and even if parliament disagreed, he could use Article 25 to dissolve it. The first President, Ebert, used it Article Forty-Eight 138 times when in office. He set a precedent to use it and his successor, Hindenburg, used it regularly during the Depression years. His Chancellor, Bruning, was forced to use it as the Reichstag had no workable majority and was regularly halted because of the violence and theatrics of the Nazis. It got to the stage where the Reichstag hardly met, the president decree used increasingly more.

Yet the 1928 election only gave the Nazis less than 3% of the vote. Without the Depression, the fact that only four years later they were the largest party would never have happened. However, Evans does not put Hitler’s success down to the failure of the Weimar governments to deal with their economic problems. Instead, it was the rise of the communists which drove people from all classes to vote for the NSDAP. As the Nazi vote was declining in 1932, the communists (KDP) was growing. This led to the conservatives appointing Hitler as chancellor.

David T. Murphy argues that German public opinion was generally against all the foreign policy decisions of the Weimar Republic. The reason was that the acceptance of the Treaty of Versailles remained in place despite the amendments made.

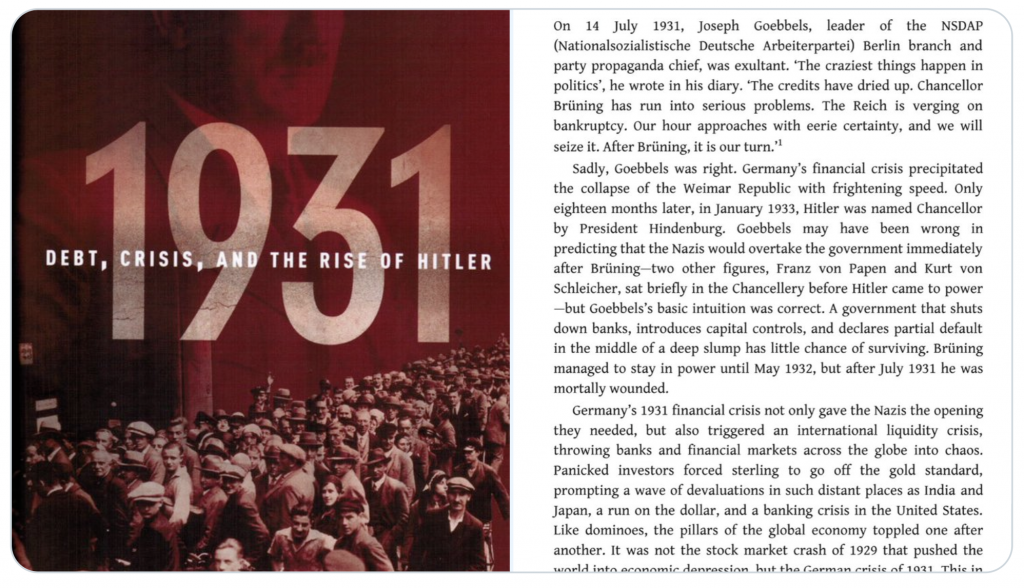

Tobias Straumann explains the following in his book ‘1931’,

Hans Mommsen, in the Rise and Fall of Weimar Democracy, writes

Stephen Lee, in The Weimar Republic, writes

Anthony McElligot in the Short Oxford History of Germany – Weimar Republic

Dirk Berg-Schlosser argues that the stronger democracies of the 1920s survived the 1930s economic crises and kept their political systems. Those countries in which democracy was relatively new tended to adopt more authoritarian systems as their solutions to the Depression. Several had already turned away from democracy because of the fallout from the First World War: Spain with Primo de Rivera, Mussolini in Italy and Pilsudski in Poland. They were to become ominous signs for the 1930s as a result.

In Germany, political parties who disagreed with the Weimar Republic (anti-system parties) became increasingly popular in the early 1930s (60.5% in the 1932 elections). Voters had seen the coups, violence and economic crises of the early 1920s and deduced that the political system was the root cause of the country’s problems. The Depression had caused German exports to fall by 16% in 1932 (higher than any other, although their fall in GDP per capita was worse in several others) and unemployment was among the highest. The issue was that, although the Netherlands faced worse figures, they had a more robust democracy.

Berg-Schlosser also argues that the Weimar Republic imposed austerity measures, cutting public expenditure and welfare benefits, and chose not to borrow to solve the financial problems. With regards to the latter, the government wanted to maintain their international credit reputation (perhaps because of the hyperinflation of the 1920s). These measures proved counterproductive and only worsened the crisis.

Finally, Berg-Schlosser agrees with Hans Mommsen above in that,

William Penz argues that

- the Weimar leaders sought to ruin their own currency in order to reduce reparations payments.

- Interestingly, he also makes a distinction between the young and older workers; the former had seen dramatic change through the First World War and European revolutions so sought drastic reform to improve their lives. The latter had seen gradual improvements under Bismarck and preferred this model.

- The biggest flaw of the Republic was that they did not purge the old monarchical leaders from the military or government administration. One consequence of this was that they tolerated the violence from the Right as they were restricting the power of the Left. For example, between 1918 and 1922, 354 murders were carried out by the Right but only received an average of four months in prison. The Left carried out 22 murders and 10 were sentenced to death. A second consequence was that there were too many powerful individuals who did not want the new republic to succeed and sought to undermine it.

- But a huge strength of the new Germany was that they had a huge electoral turnout.