- Maps

- Timeline

- Political Parties

- The Causes – A Summary

- Paul Preston

- Gil Robles

- Manuel Azana

- Largo Caballero

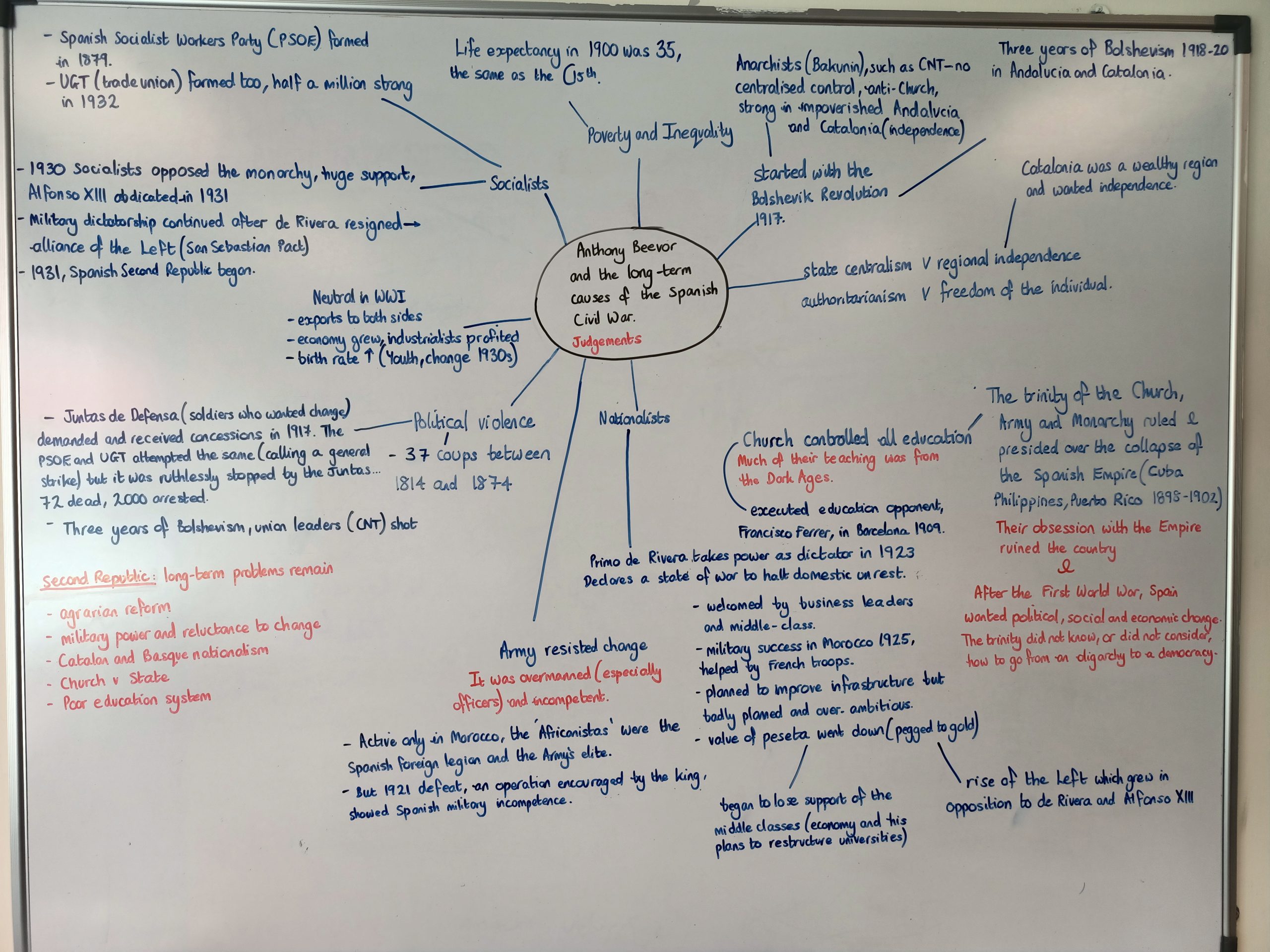

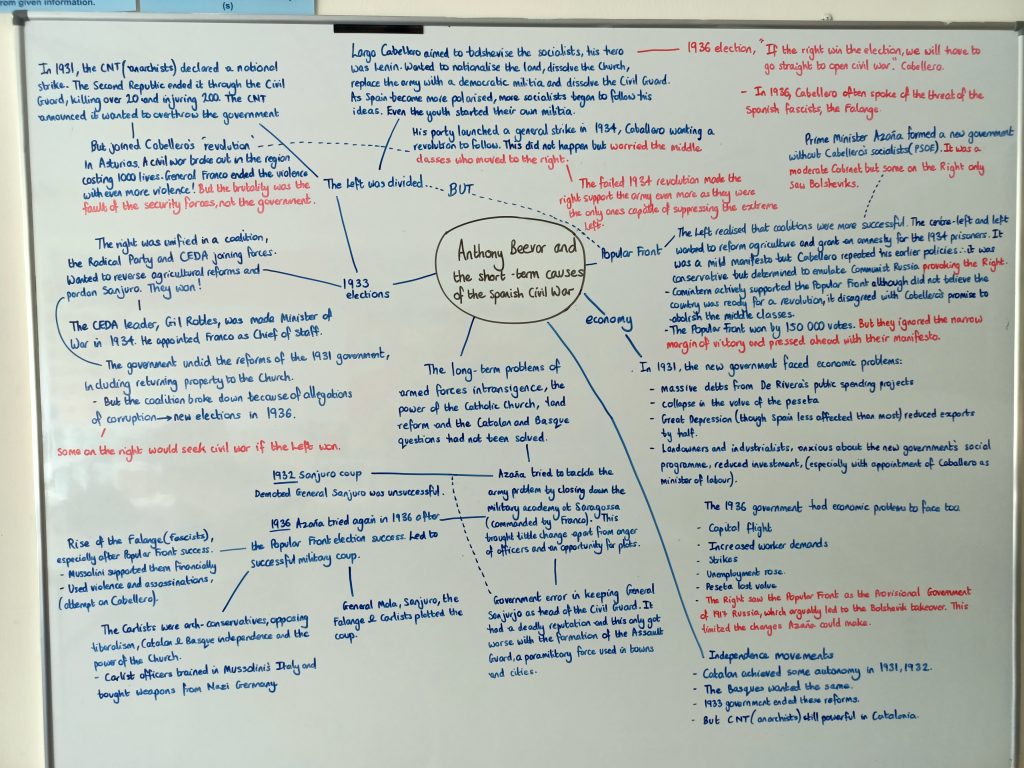

- Anthony Beevor

- Revision

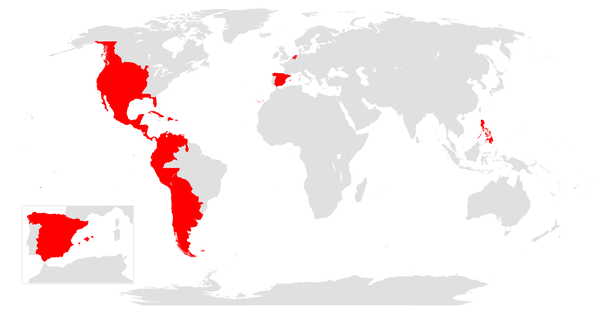

Maps

Map of the Spanish Empire

Timeline

1876 – Spain becomes a constitutional monarchy

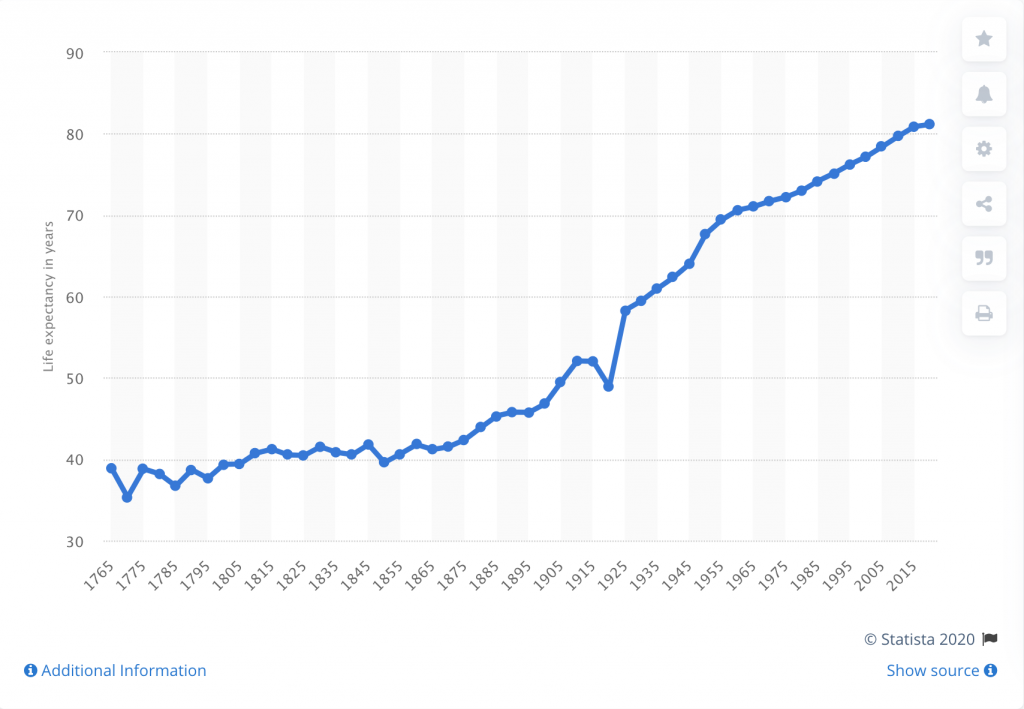

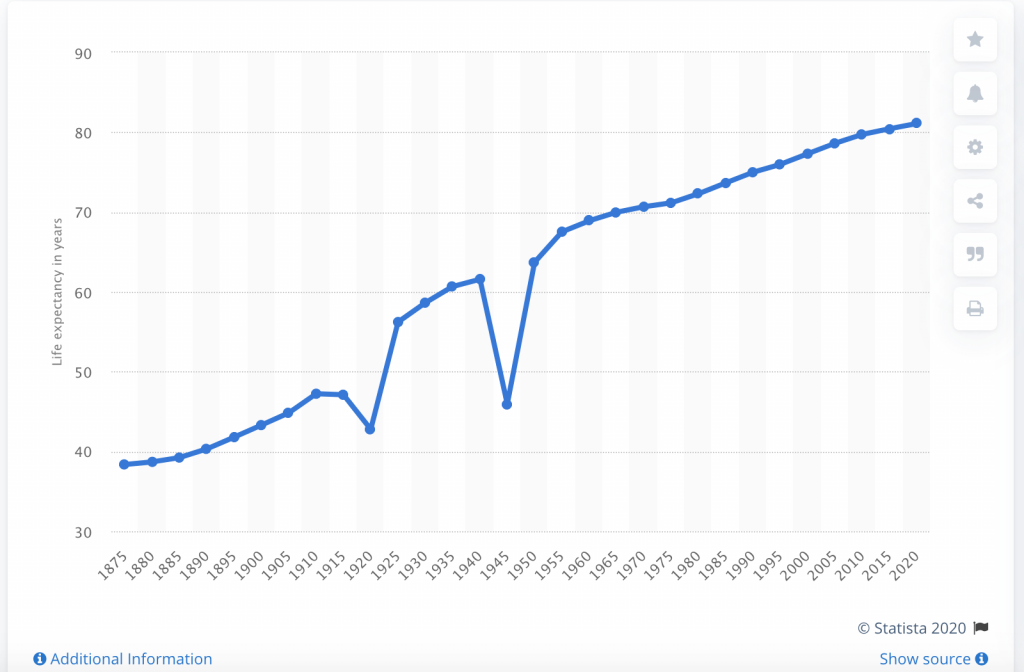

1900 – Life expectancy in Spain is 35

1917 – Russian Revolution

1918 – Three years of Bolshevism begins

1921 – Spain defeated at the Battle of Annual

1923 – Primo de Rivera launches a successful coup and establishes a dictatorship

1925 – Victory in Morocco.

1930 – De Rivera resigns, General Berenguer his replacement

1931 – Second Republic proclaimed – Zamora is president and Azana is prime minister, King Alfonso abdicated. Law of Municipal Boundaries

1932 – Unsuccessful uprising by General José Sanjurjo. Agrarian Land Reform, trade union UGT has 500 000 members

1933 – Right-wing parties form the government (led by Gil Robles) after elections.

1934 – Asturias uprising

1936 – Popular Front win elections and form a new government. A military coup leads to civil war.

Paul Preston explains that the war began on 18 June 1936 although the army coup was the evening before.

Political Parties

CNT – Formed in 1910 by Spanish workers, it was dominated by anarchist militants aimed at overthrowing the monarchy and decentralising the country. Primo de Rivera opposed the CNT and it hid in secret during these years. The organisation grew to become two million members by 1936.

UGT – Founded in 1888, this was a socialist trade union led by Largo Caballero. He became minister of labour in 1931, part of Primer Minster Azana’s government. The UGT became influential in Spanish politics, mediating in labour disputes with the government, even de Rivera. But they would not work with the CNT, arguing that it was too extreme and influenced by the Russian Bolsheviks.

PSOE – Founded in 1879, it was led by Pablo Iglesias and from 1925, Largo Caballero. The organisation grew in strength in the 1920s and by 1931 was the largest political party. They participated in coalition governments from 1931 to 1936 and were strong supporters of the Republic during the civil war. In 1921, the party was split along ideological lines with the extreme left leaving to form the Spanish Communist Party.

CEDA – Founded in 1933 and led by Gil Robles. This was right-wing party formed in response to the growing power of the left. In the 1933 elections, CEDA won the most seats but President Zamora refused to allow Robles to be prime minister. However, seven members of the party became ministers and began overturning the policies of the previous government. Most CEDA member supported the Nationalists during the civil war.

Carlists – Formed in the 1920s, the Carlists were opposed to liberalism and both political and economic modernism. It received support from the Catholic Church in the 1930s and grew to 30 000 youth members (10 000 armed) by 1936. They later allied with the Falange movement and were part of Franco’s coalition government.

Falange – Formed in 1933 by the son of de Rivera, Jose Antonio. It opposed Marxism and aimed to be a fascist state along Italian or German lines. It was not a major force before 1936 but became the dominant political movement of the Nationalists during the civil war. Jose was captured and executed by the Republicans in 1936 so without a leader, Franco merged them with the Carlists.

The Causes – A Summary

Life expectancy of people in 1900 was 35 years of age, the same as it was under Isabella and Ferdinand in the 15th century. For a comparison, see Britain and Germany below,

Watch the video above (ignore 4.00 to 8.55).

a. How did the First World War influence Spain between 1914 and 1918? Focus on the economy and how, although it brought wealth, it also brought inequality.

b. Why were there so many strikes in Spain and what was the reaction of the government, army and the right?

Read the following until Paul Preston, what were the key political, economic and social causes of the civil war?

- The Spanish Civil War has its roots in the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917. Anthony Beevor, The Battle for Spain

- The country had benefitted economically because of the First World War (getting rid of the national debt for example) but there were still huge political divisions, there were ten different governments from 1917 to 1923. These years were extremely turbulent for Spain.

- Spain was politically divided after the First World War. A dictator, Primo de Rivera, took power in 1923 and ruled until 1930. This further polarised Spain.

- The monarchy under King Alfonso XIII was forced to abdicate and flee into exile in 1931. Spain was now a republic (the Spanish Second Republic) but support for it was not unanimous.

- The Republic had gained power in 1931, the left believed that the elite (Church, landowners, Army) had too much power and wealth. Other countries had made progress in the twentieth century, but Spain, with too many agrarian poor, had not. The King was seen as an obstacle to making progress so was forced out.

- The Army was archaic and top-heavy, it had eleven soldiers to one officer. Consequently, the new republic wanted to reform the military and this was met with some resistance.

- As the Republic was liberal and progressive, Catalonia saw the opportunity to gain independence. It had become part of Spain in the eighteenth century but now wanted to be free. It was economically strong with a successful port and a growing textile industry. When the Republic granted Catalonia ‘home rule‘ or semi-autonomy, together with the military reforms, this brought the conservatives and army together in opposition to the government.

- As the Catholic Church was seen by some as wielding too much power, convents, monasteries and other buildings were attacked or destroyed.

- The right returned to power in 1933 and ruled for three years. They undid the work of the previous government and divisions in the country continued to grow. When the left united to form the Popular Front in 1936, some on the right responded with a military coup and war broke out.

Paul Preston

Long-term Causes

Paul Preston argues in ‘A People Betrayed‘ that the Spanish army felt that it was their role to hold the country together. The loss of empire in 1898 (losing the Philippines and Cuba to the USA) was the fault of the politicians, they did not adequately supply the army. This feeling was instrumental in creating a forceful reaction to politicians who sought drastic change or wanted separation from the country (Catalonia, Basque region).

In the nineteenth century, Spain was seen from the outside as a corrupt and violent country. Even as moves were made towards democracy, corruption still meant that elections were rigged and those who had power kept it. This led to the rise of the anarchist movement from the 1860s onwards. But this, conversely, led to further violence as the political classes used repression and violence to put down any anarchist strikes or protests.

Spain was neutral in the First World War and took advantage of this situation by trading with both sides. This led to a boost in the economy, primarily because of exports, but the profits were not shared. A minority grew very rich and spent their earnings on mansions, material possessions and in casinos. This was seen by the urban populations and only added to the class division within the country. However, when the war ended, the economy regressed. Preston argues that very little of the wartime profits were invested to improve Spain’s industries so that when the belligerents of the war began manufacturing again, their goods were generally better and cheaper to produce.

The trienio bolchevista of 1918 to 1920 were important years for Spain. The Russian Revolution spurred many workers to strike, take part in riots and assassinations, and even some on the extremes to instigate a revolution. The government, which was sometimes overridden by the army and with the support of Alfonso III, used force and martial law to put down this unrest. Politicians such as Maura, who had been prime minister five times, began to believe a military dictatorship was needed for Spain to solve its industrial and political problems.

The army took 35% of the country’s GDP and 70% of this was for the officers, there was one for every four men. This budget had been increased massively at the beginning of the twentieth century to ensure its support of the various governments. At a time when Spanish civilians were facing huge economic difficulties, this was unpopular. However, one consequence of this was that the army’s support was needed to sustain a government. Any thoughts of reducing this budget was extremely risky.

Primo de Rivera

The years 1920 to 1923 were turbulent for Spain, they had numerous governments as parties were unable to agree to coalitions. In 1923, Primo de Rivera (an army officer) launched a successful coup (not unusual for Spain as it had had many in the nineteenth century). He had the support from the bulk of the army and the king. This ended the 1876 constitutional monarchy.

Primo de Rivera was against Communism, Syndicalism and Separatism with the latter being the most important to him. He clamped down on the Basque country and Catalonia by making them only fly the Spanish flag, speaking Spanish and rewriting road signs to only show the ‘national’ language. This only added to the furore in those regions towards Madrid and the Spanish government.

De Rivera established a dictatorship in Spain, abolishing the Cortes (parliament) and appointing friends and supporters to key positions. Initially, his government was successful as the economy recovered from 1923 to 1926. De Rivera believed he was the saviour of Spain and that the people (mistakenly) generally loved him. However, as he centralised more and more power, and the economy began to decline, the number of opponents grew. Several small military coups failed to remove him but his unpopularity, and that of the king, began to grow. Moreover, Preston explains in detail in his book that corruption was rife under de Rivera’s government, Cabinet ministers were feathering their own nests by being both board members and awarding government contracts to these companies. This clearly added to unpopularity of de Rivera especially from 1926 when the economy began to turn.

The issue of Morocco brought de Rivera both praise and criticism. The latter because although he ordered General Picasso (uncle of the artist) to conduct an inquiry into the failure at the Battle of Annual, the results were seen as a whitewash. No blame was attached to the king for example. But when the Moroccan tribes attacked the French, fortunes changed for the Spanish as they allied with France to defeat their long-time enemies. De Rivera actually wanted to relinquish any control over Morocco, seeing it as a waste of money and resources, but the attack on the French brought a great opportunity and victory in 1925. De Rivera was a hero to Spain and had the support of the army.

De Rivera fell from power in 1930 for three key reasons. Firstly, he tried to reform sections of the army, especially the artillery and engineers, aiming to appoint officers on merit rather than length of service. When de Rivera asked for support in 1930 from the army, his previous actions meant that it was not strong enough to keep him in power. Secondly, he sought to reform universities in Spain. He introduced a policy whereby Catholic universities were able to offer degrees, this provoked a backlash from students and professors at the mainstream universities who felt that they were being undermined. De Rivera also targeted the professors who he believed were sympathetic to republicanism and socialism. Thirdly, the value of the peseta declined. His economic policies were blamed for this.

General Berenguer was chosen as the successor; he overturned some of the repressive measures of de Rivera and promised to return to the 1876 Constitution. However, the opposition to the current dictatorial system had grown too much. Opposition political parties and trade unions began to work together, uniting behind the formation of a republic. Even though Berenguer promised fair elections, no-one trusted this because of Spain’s recent history of rigged or corrupt elections. He resigned in 1931 after only a year in power. Admiral Bautista Aznar-Cabañas replaced him but he was gone after only two months, the pressure for a change was too much. It also forced King Alfonso XIII to step down although he did not abdicate immediately. He hoped it would only be temporary and his supporters would soon put him back on the throne…this did not happen!

An alliance of former liberal monarchists, Catalan politicians, and Republicans agreed to overthrow the government. This coup was peaceful and the municipal (local) elections that followed in April 1931 saw huge support for the new government.

Short-term Causes: Second Republic

1931 to 1933

In general, the right did not accept the new Second Republic. There were several reasons:

- The Church only wanted Catholicism as the Spanish religion, the Republic disagreed. Conflict therefore ensued. Churches were attacked and religious leaders spoke out against the new government. Anti-clerical policies also led to a disunity in the coalition government. For example, prime minister Niceto Alcalá-Zamora resigned, along with …, over the government decision to introduce Articles 24 and 26 of the new Constitution. They forbid

- The Second Republic allowed a degree of regional autonomy. This was especially true for Catalonia. Remember that the army after 1898 felt that a united Spain was the only way forward for the country, this belief had not gone away and Preston argues this was a key reason why the government faced opposition.

- The Latifundia’s were unhappy with some of the reforms passed by the new government. In particular, the Law of Municipal Boundaries in 1931. This meant that landowners could not bring in workers from outside of their municipality if they had any unemployed. They usually did so when strikes broke out in their own as it would force the workers to back down or lose their jobs. This new law prevented this and gave power to the workers and unions. They were also successful in obtaining an eight-hour day.

- Azana, the Minister for War, attempted to reform the army. He wanted a military that was outside of politics and cost-effective. Importantly, he had the support of some members of the army, notably the artillery and engineers who ‘suffered’ under de Rivera’s dictatorship. One key policy was to close the military academy at Zaragoza, as General Franco was the director there, he became a casualty of Azana’s policy and an enemy of his too.

Did the Second Republic go too far with its reforms? Would a gradual programme of change produce more political and economic stability and prevent a civil war? But the Second Republic needed to pacify their supporters with economic and social change, they needed funds to implement them too. A gradual rebalancing of the country’s wealth would not be enough so something more radical was chosen.

In addition to its opposition, the Spanish Second Republic also made its own errors:

- The moderates and the left disagreed about religion. Initially, the Republic was a provisional government. From October 1931, the Socialists and Leftist Republicans split with the moderates over the issue of the Church. The former began to target the Church, banning Catholic schools and turning a blind eye to attacks on religious buildings and personnel. One consequence of this was the formation of the Acción Popular.

- Some on the right decided to take action and try to rid Spain of the new government. General Sanjurjo launched a coup in 1932. It was badly planned and failed but showed the division in the country. The ringleaders could have been executed but were given long prison sentences instead. But it was of little surprise that the 1933 rightist government gave them amnesty.

1933-1936

- The 1933 elections were not fair. Boundary changes and gerrymandering had meant that the right only needed on average of 15000 votes for a seat whereas it was 34000 for the left. But the left was split in the 1933 election compared to 1931. The reforms which parties on the left wanted passed were limited in their success therefore by 1933 some had moved to more extremist parties. On the other hand, the right was more united, better funded and campaigned more professionally.

- CEDA (modelled on Mussolini’s fascists and led by Gil Robles), were the most popular party in the 1933 elections but did not have sufficient support to form a government.

- The government began to undo the legislation from the past two years. This included overturning the Law of Municipal Boundaries and developing stronger links between the clergy and the state. The former led to landlords bringing in cheap Portuguese and Galician workers which undercut the wages of the Spanish. They also took advantage of the repeal of the eight-hour day. Unemployment, poverty and hunger ensued.

- One consequence was that the trade union FNTT launched a national strike in the summer of 1934. They were warned not to do so by leftist leaders as it may be seen as revolutionary…it was and the government clamped down by arresting thousands of leaders and taking them hundreds of miles away without any provisions. Gil Robles had influenced the government in this move, he wanted any strike made illegal. Although only those which were seen to have a political agenda were outlawed, CEDA and Robles saw all as politically motivated.

- Foreign powers were involved in the rising tensions in Spain as Mussolini helped train and equip the right. For example, a militia group of 30 000 within the Carlists was ready for action by 1936.

- Caballero made a number of statements about revolution but they were generally theoretical, not really referring to the events in Spain. As such, Preston argues that they were without substance and only used by the right to scare people about a Marxist takeover.

Evaluation of Paul Preston

Paul Preston – Value

- Cited by many other historians as an expert on Spain.

Paul Preston – Limitations

- Perhaps his analysis is too one-sided. For most of his book, he blames the right for the civil war. He admits he is left-leaning in his politics so perhaps this influences his analysis. Anthony Beevor’s book

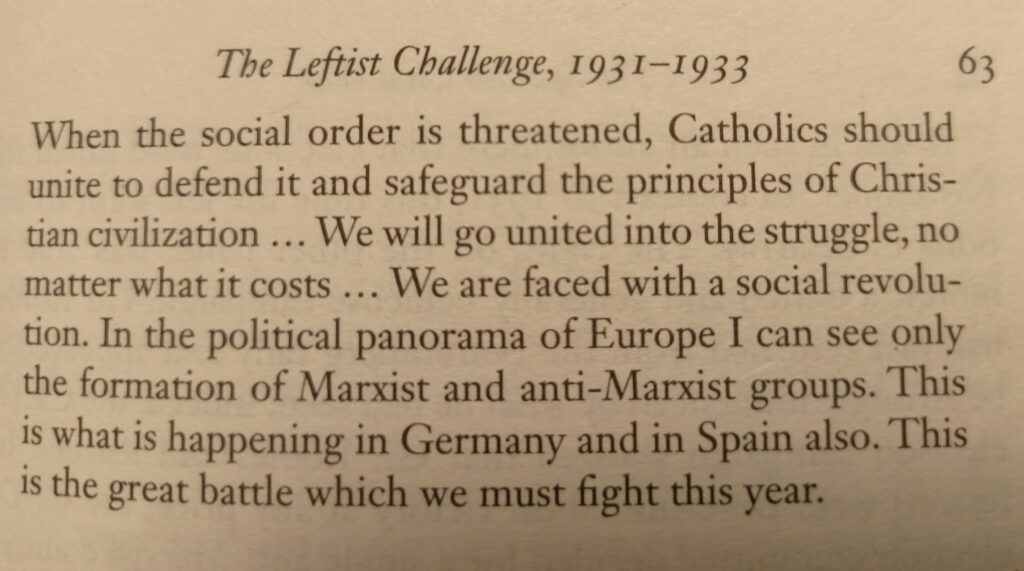

Gil Robles

- Gil Robles was a clever and dynamic leader who created an organisation called Acción Popular in 1930. This had links to the ACNP meaning that it had a Catholic and professional, especially media, influence. It portrayed the Second Republic land reforms as detrimental to both smallholders and the latifundias. It was also presented as an instrument of the Soviet Union.

- CEDA and Robles saw their quest as similar to that in Germany with Hitler. They admired how he had rid Germany of the socialists and communists, Robles even attending a Nuremburg Rally in 1933, and tried to mirror the party along Fascist lines.

- Gil Robles also wanted to destroy Basque and Catalan separatism, and was extremely critical of the Asturias Rising of 1934, calling for the death of its leaders.

- President Zamora (1931-36) did not invite Robles to form a government in 1933 despite his party, CEDA (formed in 1933), was the largest party in the Cortes (Spanish parliament). Alejandro Lerroux (leader of the Radicals) was chosen to be prime minister although CEDA was very much in charge.

- In 1934, Robles was appointed Minister of War as the Radicals hold on power was weakening. In this position, he purged the army of loyal Republican officers and appointed opponents to high-level positions. One key figure was General Franco who was made Chief of General Staff (this was important as he was able to form relationships with other senior military officers). Robles also instigated a number of army reforms, such as motorisation and equipment procurement, preparing it for the conflict ahead.

- When the war began, Robles thought that he would be a key political figure in the nationalist cause. However, Franco was still bitter that Robles was his superior a few years earlier and kept him away from power. He lived in exile for most of Franco’s reign.

Manuel Azana

- Manuel Azaña was Prime Minister of Spain from 1931-33 and 1936.

- As Minister of War (also 1931-33), he prepared reforms for the army, cutting down the inflated officer corps and making it more efficient. This would weaken it as a political force.

- It was a generous policy, retiring eight-thousand officers on full pay but the military hierarchy was displeased at other reforms such as demoting some who were seen to be overpromoted (Franco) and the closing of the General Military Academcy at Zaragoza (of which Franco was in charge). The rightist press and army hierarchy made Azaña enemy number one as a result.

- Preston argues that the reforms that Azaña put forward actually improved the army, ironically possibly making it stronger for the war ahead.

- Azaña was fearful of Lerroux’s appointment of three CEDA ministers to government, he thought it was a step towards fascism. There is evidence that Robles was intent on establising it in Spain.

- Azaña was imprisoned for a brief time because the left attempted a revolution in 1934 and he was wrongly implicated. On release, he planned to put together a Popular Front, a coalition of the left. He was only too aware that the Second Republic failed because there was disunity.

- There was a series of gigantic meetings in Valencia, Madrid and Bilbau, attended by hundreds of thousands of people. These helped persuade Largo Caballero, the socialist leader, to put aside his differences with Azaña. Preston explains that Moscow also put pressure on him to join the Popular Front.

- The Popular Front won the 1936 election but Azaña then made a huge error. Despite President Zamura having refused to have Robles as prime minister a few years earlier, Azaña decided he was too interfering and plotted to have him removed. He was successful and then took the role himself!

- He thoroughly enjoyed the ceremonial functions and the prestige of becoming president. But it deprived the Spanish left of a very able prime minister, one that was needed at a very unstable time in the country’s politics.

Largo Caballero

- Socialist Prime Minister of Spain (Azana was president) from 1936 to 1937.

- Minister in Azana’s cabinet from 1931 to 1936, helped pass legislation to improve worker’s rights

- According to Anthony Beevor, he wanted to emulate Lenin’s revolution. In 1934, sought to nationalise the land, abolish the army and Church.

- This scared the right and only added to the polarisation within the country.

- Threatened civil war if the right won the elections in 1936.

- See Beevor’s spidogram below.

Anthony Beevor

Revision

Kahoot – Causes of the Spanish Civil War